This post was written by Lesley Brooks and Amanda Boczar

The Women’s Labor Movement in the United States

The twentieth century marked a watershed century for the women’s labor movement, starting with the progressive era and evolving as world wars and the women’s rights movements reshaped how society responded to a gender-integrated workforce. As we continue to celebrate the history and accomplishments of women, this week we’re taking a look at this evolution through documents.

Digitized primary sources provide access to archives for students across USF and beyond. In fall 2021, Special Collections created in-person and virtual sessions for Dr. Cassie Yacovazzi’s HIS 6939 Seminar, “Women & Work in America since 1870.” The digital exhibit was created using archival documents to share the significance of primary sources with history majors. The full Women & Work exhibit captures key elements of that course in a curated virtual space that can be freely accessed by anyone. It offers a sweeping overview of Special Collections holdings related to the theme of American women and labor issues since the colonial era, including high-resolution full-text scans of the documents discussed above.

Overworked Women and Girls

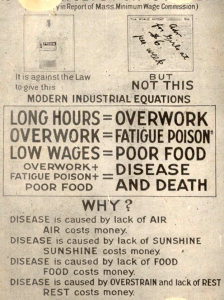

Based on materials presented at the Panama Pacific Exposition in 1915, a pamphlet titled “The Waste of Industry: Overworked Women and Girls” offers a raw and fascinating look into the 20th century movement for the legal protection of women. The inclusion of both photographs and data makes this small pamphlet an incredibly useful resource for researchers of the Progressive Era.

Published by the National Consumers’ League, the document focused on the impact of poor working conditions of women and children, the document emphasizes low wages in contrast to high risks of bodily harm. Low wages of $6 per week for extensive hours led the authors to include their “Modern Industrial Equations,” that “Overwork + Fatigue Poison + Poor Food” would result in “Disease and Death.” For them, a bottle of poison was equal to a $6 per week salary.

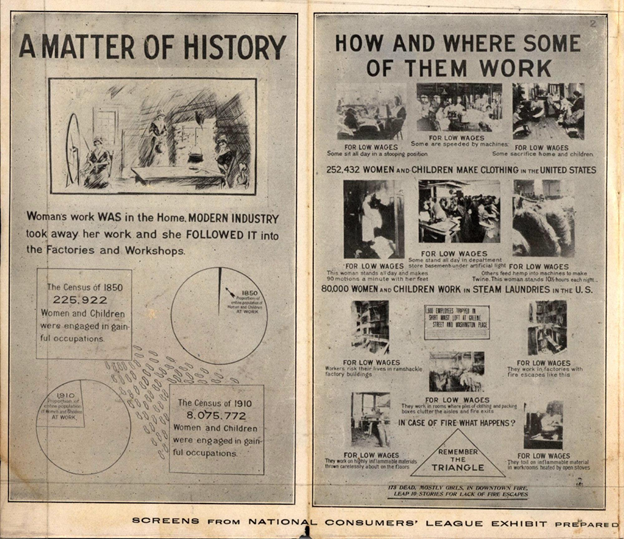

“The Waste of Industry” is not against women in the labor force and acknowledges the incredible growth between 1850 and 1910.[1] A by-line on the cover reads, “Some reasons why protective laws for women in Industry are necessary.” The majority of garment sewers in the United States at this time were women and children, a trend that continues globally into the modern era.[2] For American labor activists, the relationship between pre-industrial domestic work and the poor conditions of textile factories created a useful talking point as “a matter of history.”

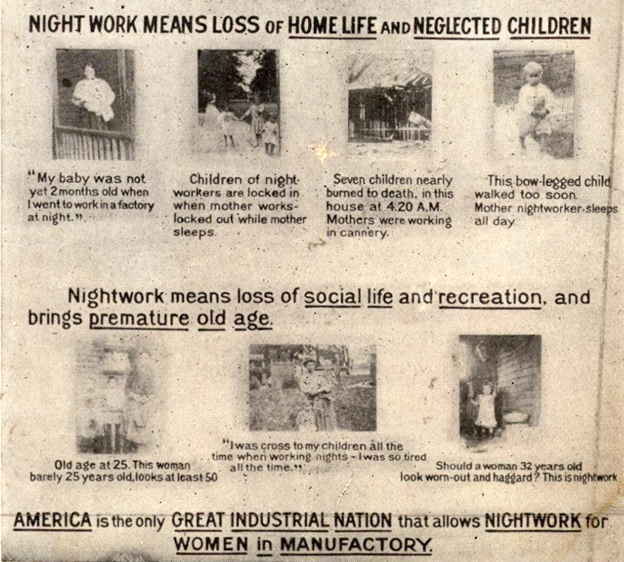

As a product of its time, “The Waste of Industry,” still placed the burden of domestic duties onto the mother. In making arguments to improve labor conditions like eliminating “night work,” the authors appealed to the reader’s sense of concern over their children. One sensationalized section reads, “Seven children nearly burned to death, in this house at 4.20 A.M. Mothers were working in cannery.”

Throughout the pamphlet, the National Consumers League boldly stresses its mission, concluding “All this is for the immediate relief and lasting benefit of women in stores and factories.” Progressive Era efforts, like this one, struggled to find balance between justifying why women and children should continue to work while supporting their ability to do so in safe and ethical ways.

Feminism, Leadership, and Policy

Forty years later, the conversation still centered on low wages for women. Concentrating on women’s rights advocacy in the areas of labor, education, and voting rights, women were working to decrease the gendered wage gap in the 1960s, as seen in the Hillsborough County League of Women Voters’ Papers (1921-1980). This collection contains materials related to women’s rights advocacy, mostly focused on Hillsborough County or Florida, like minutes from meetings, correspondence, general publications, the League of Women Voters of Florida’s State Board Report, and literature relating to the Florida constitutional revision in 1968, labor, education, and the consolidation of the governments of Hillsborough County and the City of Tampa.

Two documents from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Labor Standards Administration, Women’s Bureau provide a snapshot of the wage gap for women and women of color in the late 1960s. Titled “Fact Sheet on the Earnings Gap” and “Fact Sheet on Nonwhite Women Workers,” these documents show that full-time, year-round female workers consistently made less than male workers:

For example, in 1955 women’s median wage or salary income of $2,719 was 64 percent of the $4,252 received by men. By 1966 the proportion had dropped to 58 percent, where it remained through 1968. But, in 1989 women’s media earnings of $4,977 were 60 percent of the $8,227 received by men.

To further highlight the size of the gap, the report found that 51% of female workers in 1969 earned less than $5,000 a year while only 16% of male workers earned less than $5,000 a year.

The wage gap varied by occupation group and education level. When looking at occupation, the largest gap remained for sales workers where women earned only 41 percent of what men earned. This lack of equality extended to education level. Female and male workers who had the same amount of education received drastically different salaries. On average, women with a grade school education or 1 to 3 years of high school education were paid 56 percent less than men with the same level of education.

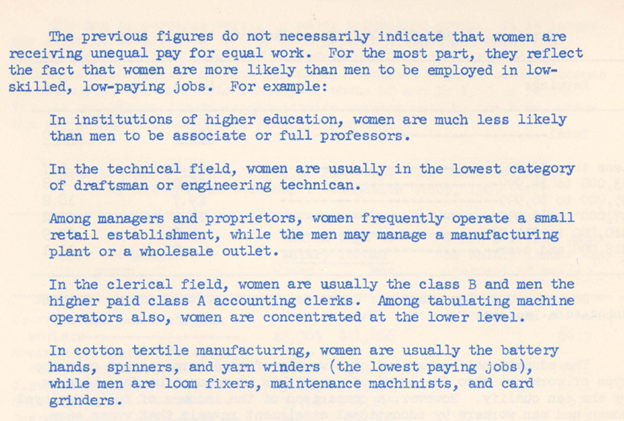

The report stressed that this evidence did not necessarily support the conclusion that women were “receiving unequal pay for equal work,” but rather that women were more likely than men to be employed in low-skilled, low-paying jobs.

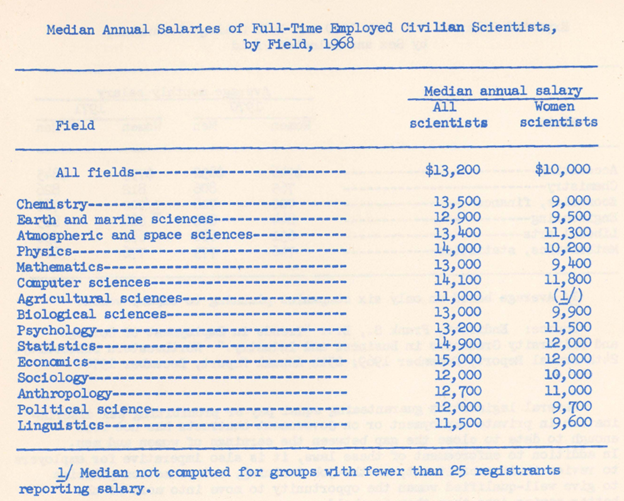

However, this statement does not hold true for professors, instructors, or scientists. In the sciences and in the institutions of higher education, women were consistently paid less than their counterparts:

In these institutions in 1965-66 (the latest data available), women full professors had a median salary of only $11,649 as compared with $12,768 for men. Comparable differences were found between the salaries of women and men associate professors, assistant professors, and instructors.

This pattern of unequal pay for equal work continues when looking at the median salaries of female scientists in 1968. On average, the wages of female scientists were $1,700 to $4, 500 less than those of male scientists in their respective fields. The report notes that the “greatest gap was in the field of chemistry, where the median annual salary of women was $9,000 as compared with $13, 500 for all chemists.”

The report ultimately acknowledges that “federal legislation guaranteeing equal pay or prohibiting sex discrimination in private employment or on Government contracts has not been enough to date to close the gap between the earnings of women and men.” In addition to enforcing laws already in place, it calls for changes in employer mind-set, asking them to “review their recruitment, on-the-job training, and promotion policies to give well-qualified women the opportunity” to advance.

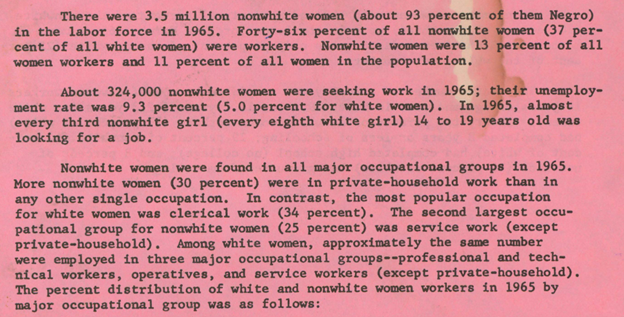

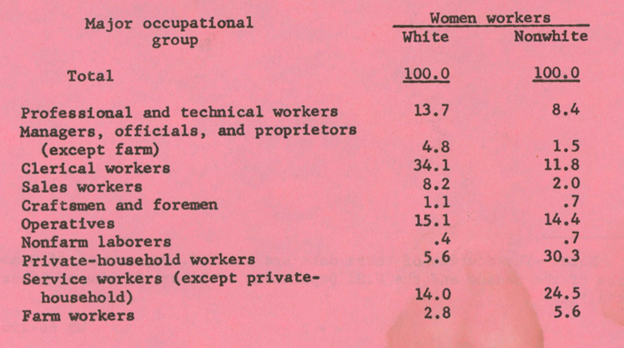

A similar report from April 1966, titled “Fact Sheet on Nonwhite Women Workers,” recognizes the struggles of women of color in the workforce. The report notes that while social, economic, and political developments have helped improve the status of women of color, there are still “substantial differences between nonwhite and white women.” In fact, there were more women of color than white women in the workforce at the time, and non-white women were more likely to be working wives and mothers. Even though the non-white female workforce made up a larger percentage of the female workforce, they experienced “higher unemployment rates, lower income, and less schooling than white women, and more of them are concentrated in low-skilled, low-wage occupations.”

Like the gendered pay gap, this racial pay gap also affected which jobs women of color were likely to be chosen for. The report found that women of color were more likely to have the occupation of “private-household work than in any other single occupation.” White women, on the other hand, were more likely to hold a clerical position. In addition, the median wage of women of color for full-time year-round work was $2,674 in 1964, 69 percent of that of white women ($3,859).

While this pay gap is not quite as drastic as the gendered pay gap, it is still significant and is made even more damaging when compounded with the gendered pay gap and inequality in occupational opportunities.

Documents, like these, provide invaluable historical information while also providing a glimpse into the day-to-day experiences and struggles of women in the past. By digitizing these documents, photographs, and pieces of ephemera, libraries can preserve these important items and make them available to researchers, historians, and students.

To view more sources in action, please explore USF Libraries’ Special Collections’ exhibits and virtual instruction sessions.

Celebrate Women’s History

Discover more compelling stories by reading Digital Dialogs’ celebrations of Women’s History Months past.

2018: What Jane Saw

2018: What Jane Saw

This article focuses on What Jane Saw, an online time travel experience to two museum exhibits that were held in the same exhibition space and visited by Jane Austen. Two hundred years after Austen visited the exhibits, this project recreates the rooms and the artwork as they could have appeared during the exhibitions.

2020: Burgert Brothers Collection of Tampa Photographs

2020: Burgert Brothers Collection of Tampa Photographs

This article traces the history of women working in Tampa’s cigar and cigarette factories as well as women’s collegiate education starting in the early 1900s. From poor working conditions, harassment, and prejudice to sexism and social norms, women faced a variety of challenges as they entered into these working and learning spaces.

2021: Celebrating Women’s History Month with Snapshots of the Florida Citrus Industry

This article traces the history of working women in the Florida citrus industry through digitized items housed in USF Libraries’ Tampa Special Collections.

2022: Womyn’s Words and the Women’s Energy Bank Collections

This article highlights the important work of the Women’s Energy Bank in the Tampa Bay area, the pioneering publication Womyn’s Words, and the contributions of Edith “Edie” Daly, Lee Anne “Oak” Wojtkowski, and Patricia “Pat” Ditto.

Additional Resources From USF Libraries:

“A Reading List of Remarkable Women in History” by Barbara Lewis, Digital Learning Librarian

“A Reading List of Remarkable Women in History” by Barbara Lewis, Digital Learning Librarian

This guide provides two bibliographies of online items in the USF Libraries catalog: 1) Women’s History lists books and videos about contributions women have made in specific fields, eras, and countries and 2) Women’s Biographies introduces women who’s names and legacies you may not recognize.

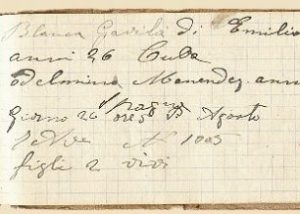

“Prolific Midwife Made Her Mark in Tampa” by Andy Huse, Special Collections Associate Librarian

“Prolific Midwife Made Her Mark in Tampa” by Andy Huse, Special Collections Associate Librarian

This article focuses on Maria Messina Greco, a local midwife. Throughout her long career, she recorded approximately six thousand names in her notepads, each one for a life she ushered into the world. The Greco Tampa Midwife Records is housed in USF Libraries’ Tampa Special Collections.

REFERENCES

[1] The number of free women in paid industrial positions more than doubled during this time period; Kleinberg S.J. (1999) Women’s Employment, 1865–1920. In: Women in the United States, 1830–1945. American History in Depth. Palgrave, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-27698-1_6.

[2] English, B. (2013). Global Women’s Work: Historical Perspectives on the Textile and Garment Industries. Journal of International Affairs, 67(1), 67–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24461672