This post was guest authored by Tomaro Taylor, Director of USF Libraries’ Special Collections – Tampa campus.

I did not grow up in a family of bakers. My mother cooks and eats out of necessity, and few things are ever the same in appearance or flavor twice. My father, on the other hand, was a true connoisseur with an expansive palate until health issues forced significant dietary changes. With these conflicting food factions in my household, it’s not surprising that I once dreamed of becoming a chef. I wanted to create foods that would amaze and awe and elicit contented sighs and empty plates no matter the diner’s palate. I was too young to decide between fine dining or confections—both seemed perfectly doable to a 10-year-old watching Julia Childs, Jacques Pépin, Jeff Smith, and Justin Wilson on TV.

My fantasies of being a chef didn’t last long. I moved on to other career interests and eventually found my own ‘ah’ in archives. Nearly 40 years later, I still enjoy cooking and baking, but I appreciate it more for its magic than its magistery. Even though science has never been my best or favorite subject, the chemistry of combining ingredients is what appeals to me most when cooking– the interplay of flavor combinations, the surprising clash of textures, the physical and emotional responses to temporary matter in its, often, unnatural state. Those are the aspects of food that keep my bookshelves stocked with cookbooks and my social media spilling over with recipes.

THE COOKBOOK

So why would a cookbook lover choose a Shaker recipe, perhaps one of the simplest forms of American cuisine? To be honest, I have always been fond of Shaker culture. Their strict adherence to ethical, moral, and religious tenets—some of which have rendered their population nearly extinct—are admirable. Plus, nothing beats a good, solid, handcrafted piece of Shaker furniture.

When I found Mary Whitcher’s Shaker House-Keeper in the USF Libraries Digital Collections, I knew my contribution to the Baking the Archives series would come from that text. What I didn’t know is that the simplicity of Shaker cuisine would prove more difficult to recreate than I would have imagined.

According to the scant information I found, Mary Whitcher (1815-1890) was a Shaker teacher whose grandfather donated much of his Canterbury, New Hampshire farm to nascent members of the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing. Although little seems to be written about Mary Whitcher, an 1849 article published in the Farmer’s Monthly Visitor describes Whitcher “as the polished, persevering instructor of female orphans, [who] has scarcely found her equal even among the most celebrated Sisters of Charity of the Catholic communion.” While Mary Whitcher’s life may not have been well-documented, it was obviously well-regarded in her lifetime.

Mary Whitcher’s Shaker House-Keeper opens with a large advertisement for Corbettt’s Shakers’ Sarsaparilla, notes on the book and the origins of the Shaker religion, and the beginning of weeks’ worth of meal planning offset by health information typically touting the benefits of the aforementioned sarsaparilla.

THE RECIPE

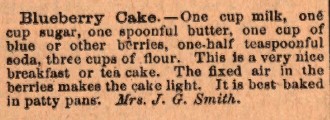

While the menu and recipe offerings run the gamut from pressed corned beef to mock oyster soup to apple tapioca pudding, I decided to try my hand at the Blueberry Cake recipe provided by Mrs. J.G. Smith on page 10. A straightforward recipe comprising 7 lines of text seemed simple enough. But, as my friend and colleague Lesley Brooks pointed out in “A Pie for Pi Day,” the recipe leaves out key information to ensure baking success.

THE BAKE

I set the oven to the moderate temperature of 350 degrees Fahrenheit, pulled out my ingredients, and added them to a bowl in the measurements and sequence described. This process was counterintuitive, as modern recipes rarely intermingle wet and dry ingredients before the final stages of preparation. To add another layer of complexity, I did not have enough all-purpose flour so I substitutes cassava flour. The texture and density of cassava flour differs from all-purpose flour. Following information found online, I used ¾ cups of cassava flour for every 1 cup of all-purpose flour.

I stirred the mixture to form a batter that was more cookie-like than cake-like. But after a moment of hesitation, during which I almost added additional milk, I went ahead and scooped the batter into a cake pan. Given the texture, I set the timer for 10 minutes.

Roughly 5 minutes after placing the cake in the oven, there still weren’t any discernible changes in the batter’s appearance. I let the timer expire and then re-set it for 20 minutes.

Around 15 minutes into the baking time, the cake was lightly fragrant but still quite pale and lumpy. I waited until the 20-minute mark before inserting a clean toothpick in my attempt to figure out if the cake was done. Instead, I learned that the cake was sizzling; the sound of melting butter and bursting blueberries was even audible with the oven door closed. Once the 20-minute mark passed, I decided to set another timer for 10 minutes. At this point, the cake had become lightly browned and blueberries near the top of the batter (the bottom of the cake) were also beginning to burst.

Once the cake reached a slightly golden color, I removed it from the oven and placed it on a cooling rack for 2 hours. I didn’t have high expectations. The cake didn’t rise much (if at all), and it seemed dense. But, it was bursting with blueberries, so I still wanted to try it.

I cut a small piece. The texture felt more like soda bread than a “very nice breakfast or tea cake.” Surprisingly, the taste was quite pleasant. Although the cake itself was not sweet, the flavors combined well enough to make the blueberries themselves taste sweetened. Just as interesting was that the flavor lingered on the palate but was not cloying or overpowering. Perhaps Mrs. J.G. Smith was right, and the cake would go well with a medium roast coffee or a lightly fragrant black tea.

I don’t know if I would make this cake again. Although it took very little time to prepare, the end product wasn’t very satisfying. Instead, I would rather take my chances on a pudding or cookie recipe, which is likely to be more forgiving.

Want to learn more about Shaker culture?

Explore books and stories by or about Shakers in the USF Libraries Special Collections:

- A juvenile guide; or Manual of good manners. Consisting of counsels, instrutions & rles of deportment, for the young.

- Lincoln’s chair: the Shakers and their quest for peace

- Love after marriage: and other stories of the heart

Want to read more posts like this one?

Explore our Baking the Archives series!