As an avid baker, I wasn’t about to let National Homemade Bread Day go by without a loaf baked in its honor. Even though bread is not my specialty, I bake bread almost every week. Usually, I dig a well-worn recipe card out of my grandmother’s or great-grandmother’s recipe box. I am no stranger to vague instructions like “bake” (no temperature or time provided) or “knead” (no instructions for how long or what the desired look is). I am also well versed in interesting measurements like “pinch,” “peck,” “bundle,” “spoonful,” or the ever-vague “handful.” While recipe basics were recorded, my grandmother and great-grandmother largely participated in an oral tradition, passing down baking knowledge and techniques from one generation to the next through conversation and experience. So much knowledge was never written down.

Unlike many of my friends, I was lucky; I began baking with my grandmother from a very early age. I was so young that I don’t even remember starting our lessons together. She wove lessons of love, patience, attention to detail, and problem solving into every bake. I cherished our time together. It’s hard to believe that she’s been gone for over 20 years now, but I still carry the lessons that she taught me and use them every day.

THE COOKBOOK

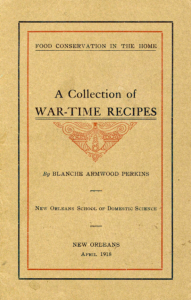

While my grandmother instilled in me a love of baking, my parents instilled a love of history. So, in search of new recipes, I turned to USF Libraries’ digital archives for some baking inspiration. That spark came after reading a previous Digital Dialogs post, Food Conservation in the Home and Recipes in the Archives by LeEtta Schmidt. The post introduced educator and social activist Blanche Armwood Perkins and her recipe pamphlet. Armwood Perkins wrote A Collection of War-Time Recipes (April 1918) with the purpose of educating her readers on the necessity for and practice of “food thrift and general economy” within the home during World War I (Armwood 8).

At the time of its publication, over a hundred years ago, the world was gripped by war and crisis. The United States asked its citizens to take great efforts to “conserve food and other vital materials to help supply the troops and our allies abroad” (National Archives, “Food Will Win the War: On the Homefront in World War I”). “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays” were encouraged while the supply chain was reorganized. The general public was supplied with many pamphlets, like Armwood Perkins’, that instructed on food conservation practices:

“The need for intelligence in home management in America was never so great as to-day, when the skillful and economical handling of food and fuel is not only necessary for the saving of income and the success of the individual home, but absolutely essential to the saving and success of the Nation.” (Armwood 6)

“Realizing the urgent need for food thrift at this time, the United States Government has …. asked [us] to save Wheats, Meats, Sugar, and Fats.” (Armwood 7)

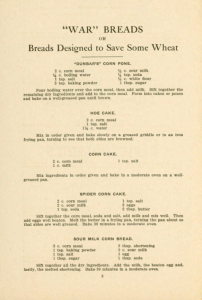

Bread production was seen as essential to winning the war. In a time where wheat was scarce, rice, potato, and especially corn were used as flour substitutes:

“Because of its ease and thoroughness of digestion, its cheapness and its mild flavor, making it combine readily with other foods, bread is rightly called ‘the staff of life.’ In the United States and in Europe, wheat is the cereal most generally used for bread-making. What flour must, therefore, be used in large quantities, in supplying bread for the armies abroad. While the nutrients in bread made by using yeast, liquid, a little sugar and fat are not so proportioned as to supply a perfect food for the body, no other food in the same quantities would furnish as much fuel and tissue building material. America produces great quantities of Indian corn, which is a grain rich in nutrients and easily made into breads … A more general use of corn in brea[d]-making will save much wheat to ship abroad. Because corn is richer in protein and fat than wheat, it is quickly attached by bacteria and molds, and is not, therefore, practical for shipment where it would be subjected to long standing in dark, damp places.” (Armwood 7)

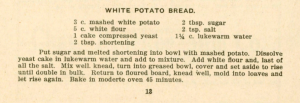

THE RECIPE

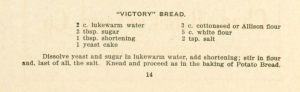

As I flipped through the recipes in A Collection of War-Time Recipes, I found an entire section on bread. One recipe in particular stood out: “Victory Bread.” Like in my great-grandmother’s recipes, the instructions were fairly vague (see “bake in moderate oven”).

I also had difficulties in sourcing some of the ingredients. While plentiful and easily accessible in the early 1900s, some ingredients, like a yeast cake, cottonseed flour, and Allinson flour, are no longer found in the typical grocery store. Luckily, Allinson flour is a brand of strong bread flour and a conversion from yeast cake to active dry yeast was easily located online. I admit that I was happy I did not have to go hunting for cottonseed flour.

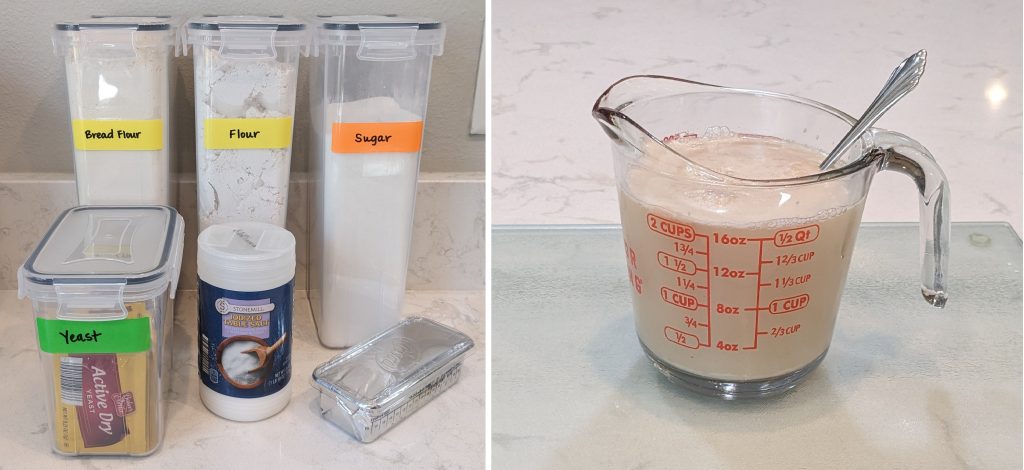

THE BAKE

As with any new bread recipe, I made one loaf instead of two, therefore halving the recipe (Armwood Perkins taught economy, after all, and there is no sense in wasting good ingredients on a large-scale recipe if it turns out to be a disaster). Unlike a lot of bread recipes I have tried, this one included shortening, which is supposed to improve sliceability, moistness, and volume. I also made the controversial decision to bake the loaf in a Dutch oven, which helps to prevent burning and uses steam to form a better crust. The outcome of this recipe was quite tasty! I’m not sure if the shortening is necessary though, as many other recipes yield similar results without the need for added fat.

It’s exciting to learn that even after one hundred years, Blanche Armwood Perkins’ pamphlet still holds valuable lessons (and recipes) for the modern baker.

Learn more:

- Celebrating Black History Month with a Portrait of Blanche Armwood

- Food Conservation in the Home and Recipes in the Archives

- A Collection of War-Time Recipes by Blanche Armwood Perkins, April 1918

- “Baking During a Time of Crisis,” the National WWI Museum and Memorial

- “Food Will Win the War: On the Homefront in World War I,” National Archives

- Historic Cookbook Collection, USF Libraries’ Digital Collections

Want to read more posts like this one?

Explore our Baking the Archives series!