As someone who works in data analytics and visualization, I had to honor Pi Day in some way. Pi Day serves to raise awareness of the importance, beauty, and relevance of mathematics and its role in shaping our world. Pi, or π, is a mathematical constant that is the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. And what is the most circular of all the desserts? Pie!

So, this year, the Baking the Archives series celebrates Pi Day with a pie… more specifically, an apple pie.

THE COOKBOOK(S)

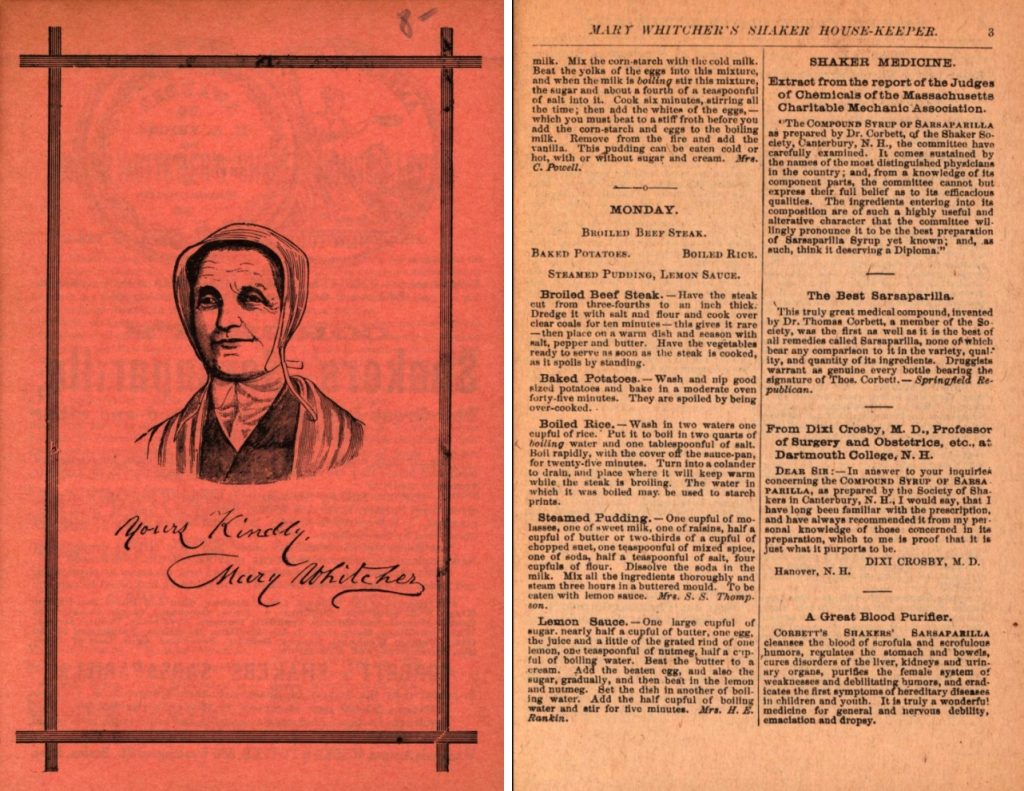

When I turned to our digital collection of historic cookbooks for some baking inspiration, one cookbook immediately stood out: Mary Whitcher’s Shaker House-Keeper, published by Weeks and Potter in 1882. Printed with a bright red cover, this booklet would have been costly to produce at the time. It contains a list of weekly recipes as well as information on the Shakers in the Shaker Village in New Hampshire (now known as Canterbury Shaker Village). Interestingly, large sections of the booklet are taken up with advertisements and testimonials for Corbett’s Shakers’ Sarsaparilla and Sandford’s Radical Cure.

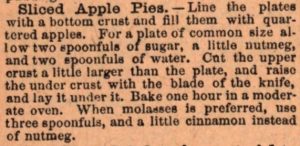

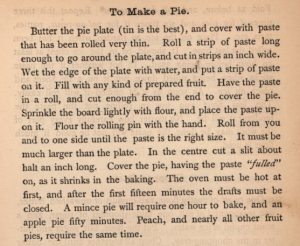

At just 36 pages and half of each page devoted to advertisements, this cookbook(let) offered sparse instructions, at best:

Mary Whitcher’s recipe for apple pie was so sparse, it did not include ingredients or instructions for making pie dough. In fact, there was none to be found in the entire cookbook. So, I turned back to the historic cookbook collection for some pie dough assistance.

Miss Parloa’s New Cook Book and Marketing Guide, published by Estes and Lauriat in 1882 (a cookbook by Maria Parloa with contributions by E.C. Daniell), couldn’t be more different from Mary Whitcher’s Shaker House-Keeper. At 434 pages, this cookbook offers descriptive instructions and even a section labelled “Marketing” which focuses on identifying and selecting cuts of meat and vegetables at the market. Published in the same year as Mary Whitcher’s Shaker House-Keeper, this cookbook did provide a recipe for pie dough… but not for apple pie! Lemon pie, check. Orange pie, check. Sweet potato pie, check. Chocolate pie, check. Frustratingly, the humble apple pie just got one tiny mention referencing the time it takes to bake one.

Did most home bakers know how to make an apple pie from scratch in the 1880s???

So, I decided to use both recipes: the pie dough recipe from Miss Parloa’s New Cook Book and Marketing Guide and the filling recipe from Mary Whitcher’s Shaker House-Keeper to create an apple pie fit to honor Pi Day.

THE RECIPE

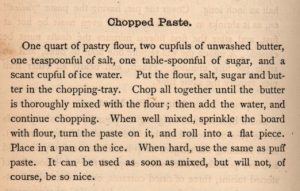

Creating an ingredient list for this pie was a challenge. Each recipe used phrases that are no longer common, 142 years after their publication. Interestingly, most recipes of the time refer to pie dough as “paste.” There’s puff paste, chopped paste, and french paste (as well as many more types, I’m sure).

For Mary Whitcher’s Shaker House-Keeper recipe, I wondered:

- What is a “plate of common size”? Is this referencing a nine inch pie plate or a dinner plate?

- How many apples?

- What measurement is a “spoonful”? What size spoon?!

- What about the pie dough?

- What temperature is referred to with the phrase a “moderate oven”?

For Miss Parloa’s New Cook Book and Marketing Guide recipe, questions abound again:

- What is pastry flour?

- What is “unwashed” butter?

- What is a “chop tray”?

- What does “place in a pan on the ice” mean?

The search for the answers to all of these questions led me down a historic rabbit hole. To answer the question “what is a moderate oven temperature” should be fairly easy. But, in the 1880s, most American homes used coal or wood fired ovens. Temperature was likely determined by feel and intuition more than by degrees.

When determining the type and amount of apples to use, I also noted the small amount of sugar used, as well as the large amount of butter. Would this recipe have been expensive to make? In the 1870s, ingredient prices were extremely low when compared to today’s prices:

- $0.10 per pound for sugar

- $0.15 per pound for butter

- $0.25 per apple

- $ 0.04 per pound for flour. [1]

That’s at least $2.00 in apples alone while the average industrial worker earned just $7.30 dollars a week:

“In 1880, the gainfully employed work force was about equally divided between agricultural and nonagricultural employments” [2]

“In 1880, the average wage for industrial workers was about $380—annually.” [3]

Written only 17 years after the end of the American Civil War, it is important to recognize the income gap between white and black workers at the time. Using census data from 1880, Ng and Virts found that:

In the South as a whole, black labor income per worker is $66.21, white labor income per worker is $74.62, and the black/white income ratio is .89. Total rural income per worker in the whole South is $71.73 for blacks, $104.03 for whites and the black/white ratio is .69 … When income from ownership of land and capital is added to labor income, the average per capita income of blacks was 61 to 64 percent of white per capita income in the South. Given that blacks were emancipated for the most part without any assets beyond their own labor, it is not surprising that in 1880, whites derived more income from the ownership of land and capital. [4]

Without knowing the average cost of salt or nutmeg in the 1870s or 1880s, this recipe would have cost around $2.20 in ingredients. That’s 0.58% of the average industrial worker’s total yearly income, or 30.14% of their weekly wage. For workers in the South, that percent was much higher: 3.32% for black labor workers and 2.95% for white labor workers. While the ingredients were fairly simple, the cost, especially for fresh apples, might have made this pie an indulgence.

THE BAKE

After gathering all of my ingredients, I went about making the pie dough. In lieu of a chopping tray, I used a pastry cutter to incorporate the butter into the flour mixture.

I refrigerated the dough (“place in a pan on the ice”) while making the filling. I used four pounds of apples for the filling. Since I’m allergic to nutmeg, I substituted it with cinnamon. I was surprised it wasn’t included to begin with. When the recipe called for “a little,” I went with “a lot” and I’m glad I did. Once the pie dough was chilled, I rolled it out and transferred it to the pie plate by rolling the dough around the rolling pin. Afterwards, I filled the pie carefully; I was determined to get all of the apples slices in there!

In the course of baking, I decided to make one large pie instead of two and sliced the apples thinly to allow for more even cooking.

I must say, the pie was well worth the 5 hours it took to make! The crust was incredibly flaky, buttery, and not too sweet. The filling was sweet and soft, but the apples didn’t fall apart. While not difficult, this recipe was time consuming. If it didn’t take so long to make, I would definitely make this pie on a monthly basis.

Explore more historic recipes:

- USF Libraries Digital Collections’ Historic Cookbook Collection

- Mary Whitcher’s Shaker House-Keeper (1882) by Mary Whitcher

- Miss Parloa’s New Cook Book and Marketing Guide (1882) by Maria Parloa

Want to read more posts like this one?

Explore our Baking the Archives series!

- Baking the Archives: Utilizing historical recipes in honor of National Homemade Bread Day

- Baking the Archives: A Pie for Pi Day

- Baking the Archives: Blueberry cake(ish)

- Baking the Archives: A sweet start for Fall

- Baking the Archives: Dead Bone Cookies

- Baking the Archives: Rum Omelet

References

[1] University of Washington. (2011). Price of Goods, 1870. Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. https://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Classroom%20Materials/Curriculum%20Packets/Homesteading/Documents/Price%20of%20Goods.html

[2] Douty, H. M. (1984). A Century of Wage Statistics: The BLS contribution. Monthly Labor Review, (November), 16-28. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1984/11/art3full.pdf (cited page 16)

[3] Azzarone, S. (2022). Heaven on the Hudson: Mansions, Monuments, and Marvels of Riverside Park. Fordham University Press. (cited chapter 7)

[4] Ng, K., & Virts, N. (1993). The Black-White Income Gap in 1880. Agricultural History Society, 67(1), 1-15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3744636 (cited p. 9-10)

Referenced: Lebergott, S. (1960). Wage Trends, 1800-1900. Trends in the American Economy in the Nineteenth Century (pp. 449-500). Princeton University Press. https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c2486/c2486.pdf