Guest post from Richard Schmidt, Collection Specialist for Digital Scholarship Services. Richard specializes in digitization of rare materials.

Years before Famous Funnies was first published in 1934, considered by some to be the first comic book as we’ve come to know it today, kids of the late 19th and early 20th centuries had dime novels to while away their free time. Dime novels were cheap magazine-sized books that serialized stories typically featuring Old West heroes, soldiers, police detectives, firemen, or adventurers. Other popular activities among youngsters in those days were going to the library and getting a strawberry phosphate at the Candy Kitchen. At least, that’s what I’ve seen in the classic film The Music Man (1962), which is probably not historically accurate.

I’ve been digitizing dime novels for the USF Libraries – Tampa Campus for well over a decade now and the first thing I noticed about them was how text heavy they are. Unlike comic books which traditionally emphasize art and action over prose, dime novels feature a short story-length word count with only a couple of drawings spread out over 25 to 30 pages. The second thing I noticed about dime novels were the horrors that people have committed to their fragile pages while attempting to repair them with tape or rubber cement. But that’s another topic altogether.

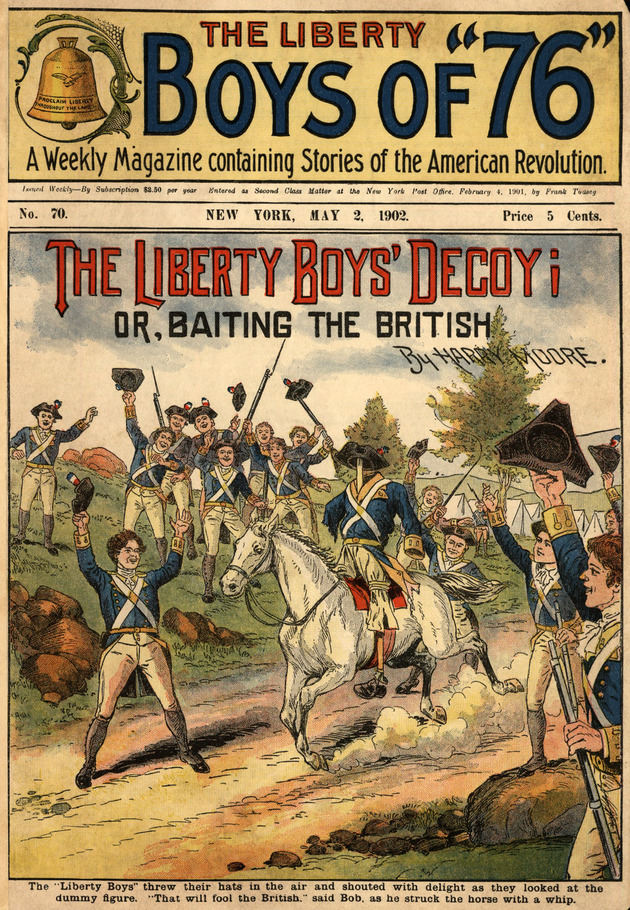

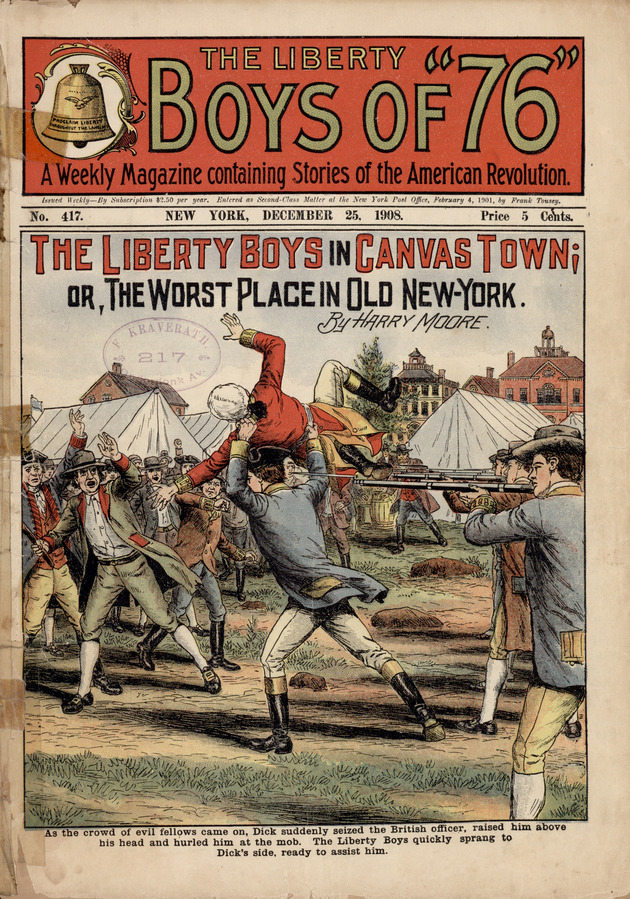

Since the 4th of July is just around the corner, I want to look at an issue of that most patriotic of series, The Liberty Boys of “76”: A Weekly Magazine Containing Stories of the American Revolution. Over 1,250 issues of Liberty Boys were published by Frank Tousey, a New York based company, from 1901 to 1925. The stories revolve around a plucky group of brave American soldiers (nicknamed “The Liberty Boys”, naturally) who take on the dastardly British and best them in every skirmish no matter what the odds. These fictionalized adventures often take place between the significant battles of the Revolutionary War.

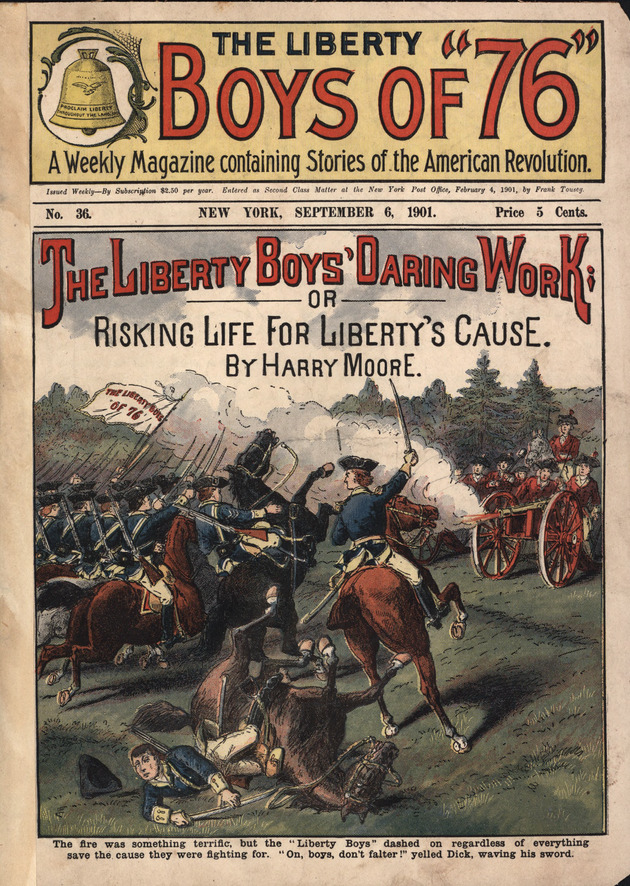

To give an impression of a typical issue of the series, I’ve chosen issue 36, published on September 6th, 1901. It’s titled “The Liberty Boys’ Daring Work: Risking Life for Liberty’s Cause” by Harry Moore. Moore is the nom de plume of either Cecil Burleigh or Stephen Angus Douglas Cox, who typically ghostwrote the Liberty Boys stories. In this tale, the “champion spy” of the patriot army named Dick Slater is asked by none other than general George Washington to sneak into the British-occupied New York City. He is to determine what their defenses are like and how many enemy soldiers are holed up in the city. Dick’s enthusiasm for yet another very dangerous assignment is palpable, and he accepts this task while his face “flushed with pleasure”. Dick stops off briefly to see his lady love in Tarrytown, which is on the way to New York City, but by nightfall he immediately sets out to start his mission in earnest.

The story gets too convoluted to elaborate upon here, but highlights include a chance meeting with General Clinton, the commander-in-chief of the British army, diving into the East River to avoid an angry mob of redcoats, and laying out a ruffian and his mates in a bar for stealing an important document. Dick continually eludes capture and death as seemingly impossible scenarios for him to deftly dodge keep popping up. Luckily, he’s light on his feet and rather adept at fisticuffs. Since his strength and agility do have their limitations, the author keeps the story interesting and somewhat realistic by not letting Dick Slater fall into the category of superhero. Primarily, he keeps one step ahead of the enemy through cleverness and keeping a cool head.

The climax of issue 36 (as promised in the cover art) is a small skirmish involving Dick and his fellow Liberty Boys taking on a small platoon of British soldiers. The patriots are victorious, but the denouement of the story is, thanks to the intelligence Dick has gathered, George Washington abandoning his plan to take back New York City from the British. Though “deeply disappointed”, that old cherry tree chopper decides on another course of action to defeat the British.

This self-contained story is surprisingly tense and easy to get wrapped up in, even a hundred and twenty years later. Dime novels may not be as flashy as their modern-day counterparts, but it’s impossible to deny that they inspire a reader’s imagination and keep reading comprehension muscles from atrophying. One never knows, perhaps Dick Slater will get his own standalone, big budget Marvel movie. Over 300 issues of Liberty Boys are housed in the USF Libraries’ digital repository.

References

- Famous Funnies (2021) Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Famous_Funnies

- Dime Novel (2021) Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dime_novel

- Lafferty, Kathy. The Liberty Boys of “76”: Dime Novel Set During the American Revolution. Inside Spencer: The KSRL Blog. https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/the-liberty-boys-of-76-dime-novel-set-during-the-american-revolution/

- Moore, Harry. The Liberty Boys of “76.”, Issue 36, “The Liberty Boys’ daring work, or, Risking life for liberty’s cause.” New York, New York: Frank Tousey, Publisher, 1901. https://digital.lib.usf.edu/SFS0036410/00053/