Today marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the largest Nazi concentration and death camp. In the weeks before its liberation, the Schutzstaffel (SS) evacuated nearly 60,000 prisoners and forced them to march to Wodzislaw while leaving 7,000 sick and dying prisoners behind in Auschwitz.[1] Suffering from starvation and harsh winter conditions, more than 15,000 people died or were killed during, what is now referred to as, the death march.[2] While an exact number is not known, it is believed that at least 1.3 million people were forced to enter Auschwitz as prisoners. Of these, at least 1.1 million men, women, and children were murdered.[3] By the end of the war, the Nazi regime, its allies, and collaborators had murdered approximately eleven million people. It is estimated that six million Jewish and five million non-Jewish individuals (such as Roma, disabled, homosexual, and Slavic people) were killed during the Holocaust.[4]

These staggering figures do not even begin to account for the number of individuals who psychologically, emotionally, and physically suffered as a result of the “systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder” of Jewish people by the Nazi regime.[5] One such individual was Alicia Appleman-Jurman (1930-2017). Her story is one of loss, terror, determination, and survival.

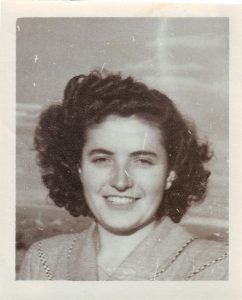

Out of her family of seven, Alicia was the only one to survive the Holocaust. Born in Buchach, Ukraine, she was the daughter of a Jewish businessman. When Adolf Hitler invaded the Ukraine in 1941, her life changed dramatically. She notes that all men between 18 and 50 were required to “register,” from which they never returned. Her father was one of these men. Later, two SS men forced Alicia and her friends to board a train. While on the train, she survived by being thrown through a window. In the ghetto, the SS began “murdering people and tossing their bodies into open graves.” Her brother, Zachary, who openly resisted the efforts of the Nazi regime, was murdered and found hanging from a tree. Another of her brothers, Bunio, was murdered as part of a “collective punishment ritual,” in which “a boy had attempted to escape … and as a deterrent every tenth boy was executed.” At the age of 12, Alicia was taken to a prison camp, beaten, and left with the dead to be buried. A Jewish man, who came to collect the dead for burial, found her barely alive and smuggled her out of the prison. Her two other brothers were also killed and her mother, Frieda, was murdered by a German solider when she stepped in front of Alicia, saving her life. Alicia was only allowed to live because the German soldier ran out of bullets; his last taking the life of her mother.[6]

The photographs in the Alicia Appleman-Jurman Photograph collection provide viewers with a snapshot of Alicia’s life after the war and document Alicia’s determination to be free, to be educated, and to help others. After the war, Alicia spent time in a displaced persons camp in Badgastein, was sent to a British concentration camp in Cyprus, and then joined the Israeli Navy.[7] Just like many other refugees, Alicia’s family and home had been destroyed but her hope was not.

Photographs, like those in our digital collections, provide powerful documentation of these atrocities and ensure that victims are not forgotten.

Discover this remarkable survivor by exploring the Alicia Appleman-Jurman Photographs.

You can also:

- Listen to her powerful lecture, collected for the Holocaust Survivors Oral History Project on May 22, 1992.

- Listen to her interview, collected for the Holocaust Survivors Oral History Project on January 25, 2010.

- Tour the “Alicia: My Story” exhibit.

USF Digital Collections have made four additional WWII and Holocaust-related collections available to the public:

- Holocaust and Genocide Studies Center Collections

- Holocaust Survivors Oral History Project

- Concentration Camp Liberators Oral History Project

- World War II Photograph Collections

Start your exploration by viewing a selection of photographs from the Alicia Appleman-Jurman Photograph collection in the image gallery below:

REFERENCES

[1] “The Liberation of Auschwitz,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C., Accessed January 15, 2020, https://www.ushmm.org/information/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/special-focus/liberation-of-auschwitz.

[2] “The Liberation of Auschwitz,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

[3] “The Liberation of Auschwitz,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

[4] “Introduction,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C., Accessed January 15, 2020, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/documenting-numbers-of-victims-of-the-holocaust-and-nazi-persecution.

[5] “Learn,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C., Accessed January 15, 2020, https://www.ushmm.org/learn.

[6] All of the biographical information in this paragraph was found in two sources: 1) the “Appleman-Jurman, Alicia” oral history interview summary on the Holocaust Memorial Center’s website: https://www.holocaustcenter.org/visit/library-archive/oral-history-department/index-summaries/appleman-jurman-alicia/ and 2) “Alicia Appleman-Jurman lecture” collected for the Holocaust Survivors Oral History Project on May 22, 1992: https://digital.lib.usf.edu/SFS0036403/00001.

[7] “Alicia: My Story Continues,” Alicia: My Story, The official website for Alicia Appleman-Jurman, Accessed January 15, 2020, https://aliciamystory.com/alicia-my-story-continues-2/.