In honor of Library Lovers’ Day, Digital Dialogs asked members of USF Libraries’ faculty and staff to share a story about a book that impacted their life. Read one of these stories below!

This guest post was written by Zibby Wilder, Assistant Director of Communications & Marketing at USF Libraries.

I grew up on a farm, before the days of computers and phones, and when I wasn’t doing chores or moseying around the property with my sweet, blind, elderly Shetland pony, I was tucked away somewhere reading. The school library was one of my favorite places, and monthly book club delivery day was my favorite day.

Because we lived in a remote area, we didn’t have a neighborhood library, so the school library was our only guaranteed resource for books. When summer break came around, my mom would bring home books she found at thrift stores or traded with friends from work. She kept an eye out for anything from the Books for Young Explorers series published by the National Geographic Society. These generally featured animals and landscapes vastly more exotic than cows, chickens, and Puyallup, Washington. They were my favorites.

One day, mom came home with one of these treasured books, and before she handed it over said, “You know how sad Ivan makes you so I need to let you know, this story will make you sad like Ivan does.” Living on a farm, we were not spared from hard truths. Sometimes it seemed as if there was as much death as there was life. My mom never shied away from allowing us to see the harsher side of life beyond our farm and Ivan’s situation was one that stoked an angry fire in my heart.

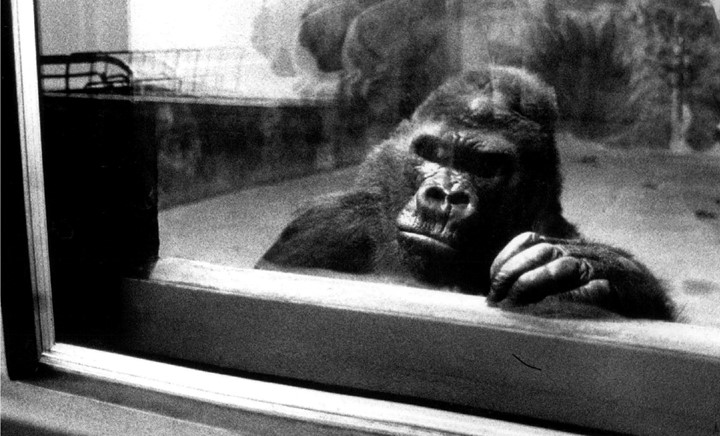

On rare days when we needed to go to the “big city”, we always stopped at the B&I. The B&I was a roadside attraction in south Tacoma–a string of shoddy buildings encasing everything you can think of at a discount. It was circus-themed and while my mom would shop, my brother and I might ride the small carousel or watch a clown tie balloon animals. Mostly, we stood silently in front of the long row of windows that looked into the 40’ x 40’ concrete cage of Ivan the Gorilla.

I didn’t know it then, but in 1962, Ivan’s mother, a western lowland gorilla in the Republic of Congo had been murdered so that infant Ivan could be sold into the pet trade. He and another infant Gorilla, Burma, were shipped to Tacoma where Burma promptly died. Soon after, when his human “family” realized gorillas don’t make for good housemates, Ivan’s owner decided to put him on display at his shopping center, the B&I. Ivan didn’t do much but sit there looking miserable amidst short bursts of screaming and pounding on the windows. Looking at him made my heart hurt. Something inside of five-year-old me flamed with anger for Ivan. Here I was, just some kid, and even I knew this wasn’t right. Intelligent, majestic, social gorillas did not belong alone in concrete cells in Tacoma, Washington.

This all seems an aside, but the point is that Ivan’s plight aroused something in young me. Some internal need to use my voice for those who can’t speak for themselves–mostly animals, because those were the friends I knew on our rural farm. We didn’t have actual neighbors, so I considered all the wildlife–and even the forests of evergreens that blanketed the steep slopes of our property–my friends and neighbors. In the area of Puget Sound where we lived, friends and neighbors included Cedar, Salmon, Mt. Tahoma, Huckleberry, Bald Eagle, Otter, Coyote, Douglas Fir, Crow, St. Helens, Blackberry, Harbor Seal, and Killer Whale.

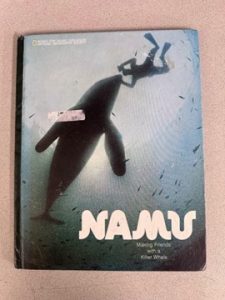

The book that was the subject of my mom’s warning had on its cover an image that really took me aback. It was of a neighbor: a Killer whale. Along with the silhouette of the whale, was a silhouette of a man. I had never seen a person swimming with a Killer whale, and this seemed like a really dumb idea, so I immediately had a bad feeling about this book.

Namu: Making Friends with a Killer Whale told the unbelievable story of a Killer whale that had been tangled in a fisherman’s net off the coast of Namu, Canada. The whale was named Namu and was sold to a man with whom the whale became fast friends. The man loved the whale and the whale loved the man. They had a lot of fun together. The end.

I was probably seven or eight years old when I first read this book and even at that tender age, could smell the B.S.

There was something so wrong with how the information in the book was presented that it broke my heart in many ways: it broke my heart that one of my neighbors had to live in solitary confinement like Ivan the Gorilla; it broke my heart that “Namu” (originally C11 of the Northern resident orca families) was portrayed more like a toy than a conscious and sentient individual; it broke my heart that the book didn’t mention the fact that C11 died after just one year in captivity.

Most of all, it broke my heart that this book made me not trust books anymore.

The story was almost legendary for its barbarity where I grew up, so I knew what happened after Namu died. Ted Griffin, owner of the Seattle Marine Aquarium and the “friend” depicted in the Namu book, organized (and profited from) a deadly free for all where men poached babies from our neighbors in the Southern resident orca families of Puget Sound. They killed five orca and sold seven kidnapped survivors to marine parks across the continent.

Books had always been places of escape for me. They contained places to escape to where you could trust the journey the author was taking you on. There was little blurring of fact and fiction. The realization that books could present misinformation as truth was new to me and, frankly, about as sad as learning there wasn’t an actual bunny delivering special candy just for me on a certain Sunday every April.

All I could do to counter my disappointment was to start writing. My career as a writer began by using every school assignment as an opportunity to report the truth. As soon as I was old enough, I began tabling and protesting for environmental organizations. Later, I became a career animal advocate, working in communications for regional, national, and international animal advocacy organizations. The work was heartbreaking and the pace of change glacial, but I helped to make change by giving voice to the voiceless.

My work told the truth of difficult stories and crafted connections that changed peoples’ minds and urged them into action. Thankfully, the world is changing, even if the change is slow. Ivan lived out the last 18 of his 50 long, lonely years in the relative freedom of Zoo Atlanta; endangered elephants are no longer shocked with cattle prods and carted around the U.S. in train cars for circus performances; chimpanzees, our closest evolutionary relatives, are no longer exploited for biomedical research; and Lolita (Tokitae), the last surviving baby from that terrible day in Puget Sound, spent the 53 years since that horrific day of her capture in a tiny, dilapidated tank of murky water. She died alone in August of 2023, but her sad and confounding story is finally forcing a showdown of science and ethics vs entertainment and economics.

Though Namu: Making Friends with a Killer Whale broke my heart, it also changed my life by shaking my beliefs and assumptions about truth and trust, experts and expertise. It taught me the importance of checking facts, asking hard questions, paying attention to small details, and never shying away from the truth–no matter how uncomfortable it might make people. I no longer work professionally as an animal and environmental advocate, but I still encounter situations where the lessons I learned from this book come into play. Unlike in my youth, we now have access to unlimited information which makes the big lesson I learned from the book Namu: Making Friends with a Killer Whale all the more essential and relevant:

Don’t believe everything you read.