In honor of Women’s History Month, Digital Dialogs is delving into the past to take a look at an early form of photography: glass plate negatives. Before photographs were printed on paper or saved as digital files, images were imprinted on metal and glass plates. Since the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, dozens of different photographic formats, techniques, and processes have been used.

The 1850s saw a rise in new photographic formats and processes:

- Ambrotype (early 1850s to mid-1880s)

- Tintype (early 1850s to early 1900s)

- Stereograph (1850 to 1900s)

- Glass plate negative (1850s to 1920s)

- Cartes de visite (mid-1850s to 1920s)

- Lantern slide (1850s to 1940s)

While daguerreotypes imprinted images on copper plates, glass plate negatives used glass as its medium. In use from the 1850s until the 1920s, glass plate negatives:

Were popular with both amateur and professional photographers. There are two formats of glass plate negatives: collodion wet plate negatives (1855-late 1880s) and gelatin dry plate negatives (late 1880s-1920s). Both types have a light-sensitive emulsion with a binder thinly layered on one side of a glass plate. [1]

Using glass and not paper as a foundation, allowed for a sharper, more stable and detailed negative, and several prints could be produced from one negative … Invented by Dr. Richard L. Maddox and first made available in 1873, dry plate negatives were the first economically successful durable photographic medium. Dry plate negatives are typically on thinner glass plates, with a more evenly coated emulsion. Dry plate glass negatives were in common use between the 1880s and the late 1920s. [2]

As photographic mediums became more stable, photography became more and more popular (and more and more accessible). Early photography subjects were vast and varied, from portraits to bridges to cityscapes. As with older artistic mediums, it is no surprise that women often became the subject.[3] Interestingly, early photography saw a rise in women not only in front of the lens but also behind it.[4][5]

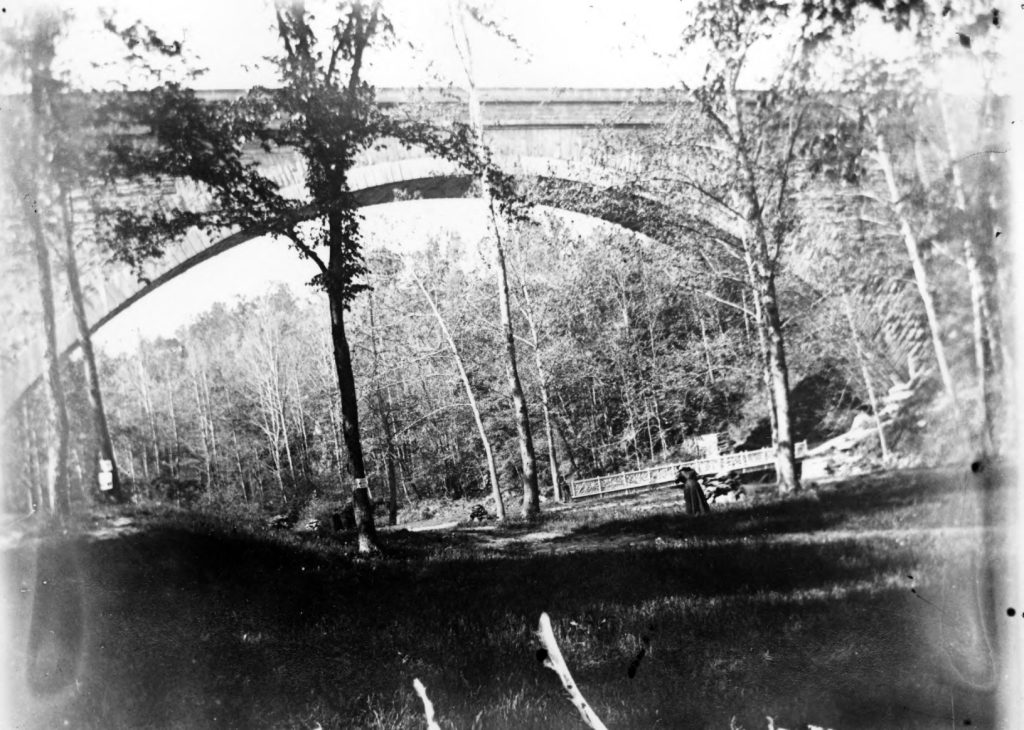

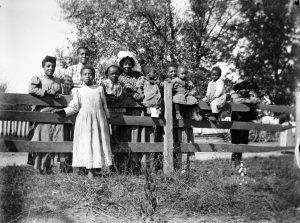

The Archibald Slaymaker Glass Plate Negative Collection, housed in the Tampa Library’s Special Collections, is an wonderful example of amateur photography. This collection is largely family-centric, documenting the home and social life of the Slaymaker family in Virginia’s Albemarle County in the 1880s. The collection includes carte de visite photographs, black and white prints, and glass plate negatives. The collection also includes the typescript of a Slaymaker family history in the 20th century written by Addison Slaymaker, a Tampa resident and the donor of this historic photograph collection.

While we, as viewers, can never know who the photographer or photographers were who created the glass plate negatives in the Slaymaker collection, we can see that their subjects are largely domestic, focusing on the home, on the family, on the people who lived nearby, on local children and families (of likely formerly enslaved peoples), and on nature. Archibald Slaymaker was named as a contributor to the collection, and likely the owner or purchaser of the photographic materials used. But, it is reasonable to assume that multiple family members may have used these materials and contributed to the creation of images.

Could some of these images been created by a female member of the Slaymaker family? Perhaps. A few images point to women using cameras and even setting up a self portrait.

As you ponder the possibilities, take a stroll through a selection of photographs from the Archibald Slaymaker Glass Plate Negative Collection below…

Celebrate Women’s History

Discover more compelling stories by reading Digital Dialogs’ celebrations of Women’s History Months past.

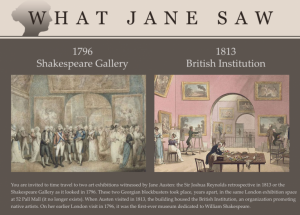

2018: What Jane Saw

2018: What Jane Saw

This article focuses on What Jane Saw, an online time travel experience to two museum exhibits that were held in the same exhibition space and visited by Jane Austen. Two hundred years after Austen visited the exhibits, this project recreates the rooms and the artwork as they could have appeared during the exhibitions.

2020: Burgert Brothers Collection of Tampa Photographs

2020: Burgert Brothers Collection of Tampa Photographs

This article traces the history of women working in Tampa’s cigar and cigarette factories as well as women’s collegiate education starting in the early 1900s. From poor working conditions, harassment, and prejudice to sexism and social norms, women faced a variety of challenges as they entered into these working and learning spaces.

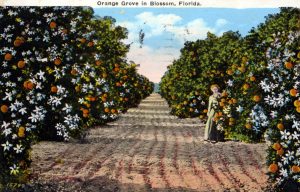

2021: Celebrating Women’s History Month with Snapshots of the Florida Citrus Industry

This article traces the history of working women in the Florida citrus industry through digitized items housed in USF Libraries’ Tampa Special Collections.

2022: Celebrating Women’s History Month with Snapshots of Women at Work

This article delves into the USF Libraries archives to explore the working conditions, pay disparities, leadership efforts, and related policies of women and girls in the early twentieth century.

2022: Womyn’s Words and the Women’s Energy Bank Collections

This article highlights the important work of the Women’s Energy Bank in the Tampa Bay area, the pioneering publication Womyn’s Words, and the contributions of Edith “Edie” Daly, Lee Anne “Oak” Wojtkowski, and Patricia “Pat” Ditto.

2023: Celebrating Women’s History Month with the Burn Bosses of Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary

This article explores the history of the female Burn Bosses of the Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary and their valuable work with prescribed fires and environmental conservation.

Additional Resources From USF Libraries:

“A Reading List of Remarkable Women in History” by Barbara Lewis, Digital Learning Librarian

“A Reading List of Remarkable Women in History” by Barbara Lewis, Digital Learning Librarian

This guide provides two bibliographies of online items in the USF Libraries catalog: 1) Women’s History lists books and videos about contributions women have made in specific fields, eras, and countries and 2) Women’s Biographies introduces women who’s names and legacies you may not recognize.

“Prolific Midwife Made Her Mark in Tampa” by Andy Huse, Special Collections Associate Librarian

“Prolific Midwife Made Her Mark in Tampa” by Andy Huse, Special Collections Associate Librarian

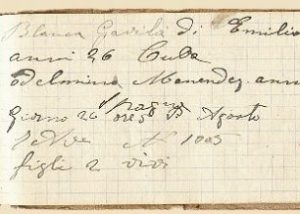

This article focuses on Maria Messina Greco, a local midwife. Throughout her long career, she recorded approximately six thousand names in her notepads, each one for a life she ushered into the world. The Greco Tampa Midwife Records is housed in USF Libraries’ Tampa Special Collections.

REFERENCES

[1] Local History and Genealogy Digital Exhibits (2023). Glass Plate Negatives: A Brief History. The Urbana Free Library. https://urbanafree.omeka.net/exhibits/show/block-exhibit/glass-negatives

[2] Oregon State University (2024, March 4). Early Photographic Formats and Processes in the Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Glass Plate Negatives (1850s to 1920s). Oregon State University Libraries. https://guides.library.oregonstate.edu/earlyphotoformats/glassplatenegatives

[3] Smithsonian (2019, June 14). Women of Progress: Early Camera Portraits. National Portrait Gallery. https://npg.si.edu/exhibition/women-progress-early-camera-portraits

[4] The Royal Collection Trust (2024). Women Photographers: The Royal Collection contains a significant body of work by women photographers. Royal Collection Trust. https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/Trails/women-photographers

[5] Mogdol, Erin (2022, April 12). What Was It Like to Be a Woman Photographer in the 19th and 20th Centuries?. Getty. https://www.getty.edu/news/what-was-it-like-to-be-woman-photographer-19th-20th-centuries/