Guest post from Dr. Matthew Knight, Associate Librarian USF Libraries, Tampa campus and Affiliate Faculty (History) at University of South Florida.

As President Biden declared March 2023 to be Irish-American Heritage Month, he noted that Irish immigrants “helped build America — never forgetting where they came from, always remembering the courage and pride they brought with them from the old country.” Missing from this rosy picture, however, is any mention of the discrimination and degradation faced by millions of Irish immigrants in the post-Famine decades from 1840–1880, a time when cultural stereotypes branded them a violent, ape-like, immoral, uncivilized, inferior race.[1] Desperate for acceptance in their adopted home, many of the Irish in America saw themselves as exiles rather than voluntary émigrés.[2]

As President Biden declared March 2023 to be Irish-American Heritage Month, he noted that Irish immigrants “helped build America — never forgetting where they came from, always remembering the courage and pride they brought with them from the old country.” Missing from this rosy picture, however, is any mention of the discrimination and degradation faced by millions of Irish immigrants in the post-Famine decades from 1840–1880, a time when cultural stereotypes branded them a violent, ape-like, immoral, uncivilized, inferior race.[1] Desperate for acceptance in their adopted home, many of the Irish in America saw themselves as exiles rather than voluntary émigrés.[2]

Perhaps nobody understood the dichotomy between adopted country and homeland better than the most prolific and popular playwright of the Victorian age, Dublin-born Dion Boucicault, who, while living in America, sought “to rescue the Irish character from the unmerited ridicule and degradation” portrayed on stage, in print, and in public opinion. “The blundering, whooping, drunken, shillelagh-twirling, ridiculous, quarrelsome fool,” he continued, was a caricature “repeated so often that the world at large believed it.”[3] And so, with motives as pecuniary as they were patriotic, Boucicault presented witty, dashing, and heroic Irish characters on stage, thrilling audiences with daring escapes, biting wit, and puckish cleverness, all the while accompanied by sentimental music and breathtaking scenery. This new ‘Stage Irishman’ dazzled Irish and Irish-American audiences, and yet was never threatening or overtly political; consequently, British theatre-goers also flocked to see this new form of Irish melodrama, and Boucicault made himself a fortune. In fact, despite writing more than 200 plays in his lifetime, it is for his handful of Irish dramas and their Irish “comic-rogue heroes” that Boucicault is best known today.[4]

USF Libraries Special Collections is home to the Dion Boucicault Theatre Collection, one of the largest publicly accessible collections of Boucicault materials in the world; and within this magnificent collection are prompt books, handwritten play scripts, and other ephemeral materials associated with Boucicault’s most famous Irish plays (“The Colleen Bawn,” “Arrah-na-Pogue,” and “The Shaughraun”), as well as his ‘minor’ Irish dramas (“Cushla Machree,” “The Rapparee,” “Suilamor,” “Robert Emmet,” and “The Amadan”). Within these manuscripts, researchers can see first-hand the annotations and amendments Boucicault made to his plays, sometimes to make them more patriotic and political for his Irish audiences, and other times to demonstrate his willingness to remove material that might offend a pro-British audience. Representative samples from this collection can be found in the newly rebooted Dion Boucicault Theatre Collection hub, where digitized prompt books, play scripts, and background material will continue be added in future.

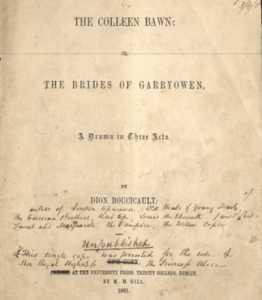

Boucicault’s first major Irish drama, “The Colleen Bawn,” was written in New York in 1860, and his international reputation soared after the unprecedented success of this play. Boucicault assumed the role of one of his most memorable Irish “comic-rogue’ heroes, Myles-na-Coppaleen, whose spectacular dive into an onstage ‘lake’ to save the drowning Eily delighted capacity audiences for decades. This type of ‘sensation scene,’ coupled with just the right amount of Hibernian flavor and character, became the template for Boucicault’s success with his Irish plays. USF Libraries houses several prompt books for “The Colleen Bawn,” and they are fascinating in their own right: one, dating from 1861, was intended as a gift for Princess Alice, whose mother Queen Victoria was a huge fan of Boucicault and his work. Another appears to be a slightly reworked version that was staged in Melbourne, Australia on Boucicault’s trip there in 1885.

Boucicault’s first major Irish drama, “The Colleen Bawn,” was written in New York in 1860, and his international reputation soared after the unprecedented success of this play. Boucicault assumed the role of one of his most memorable Irish “comic-rogue’ heroes, Myles-na-Coppaleen, whose spectacular dive into an onstage ‘lake’ to save the drowning Eily delighted capacity audiences for decades. This type of ‘sensation scene,’ coupled with just the right amount of Hibernian flavor and character, became the template for Boucicault’s success with his Irish plays. USF Libraries houses several prompt books for “The Colleen Bawn,” and they are fascinating in their own right: one, dating from 1861, was intended as a gift for Princess Alice, whose mother Queen Victoria was a huge fan of Boucicault and his work. Another appears to be a slightly reworked version that was staged in Melbourne, Australia on Boucicault’s trip there in 1885.

Boucicault’s next big hit was “Arrah-na-Pogue,” first staged in Dublin in 1864 and set during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Although the play was more political than “The Colleen Bawn,” it still managed to delight audiences when it moved to London in 1865. Boucicault’s character Shaun the Post continued where the roguish Myles left off, thrilling audiences worldwide with sensational scenes and witty dialogue. Boucicault’s reworking of the old street ballad “The Wearing of the Green,” however, was banned from British theatres after Fenian uprisings and bombings in 1867. USF Libraries houses a prompt book with Boucicault’s corrections the lyrics on the last page. To this day, it is Boucicault’s version of the song that you will hear sung, especially on St. Patrick’s Day.

Boucicault’s next big hit was “Arrah-na-Pogue,” first staged in Dublin in 1864 and set during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Although the play was more political than “The Colleen Bawn,” it still managed to delight audiences when it moved to London in 1865. Boucicault’s character Shaun the Post continued where the roguish Myles left off, thrilling audiences worldwide with sensational scenes and witty dialogue. Boucicault’s reworking of the old street ballad “The Wearing of the Green,” however, was banned from British theatres after Fenian uprisings and bombings in 1867. USF Libraries houses a prompt book with Boucicault’s corrections the lyrics on the last page. To this day, it is Boucicault’s version of the song that you will hear sung, especially on St. Patrick’s Day.

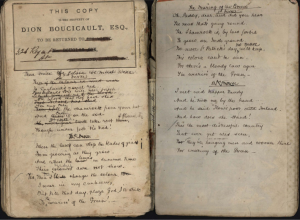

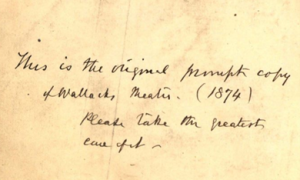

As beloved as these two Irish plays were, Boucicault’s most enduring play remains “The Shaughraun,” first staged in New York in 1874 and played as recently as 2004 at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. Although it centered on an escaped Fenian prisoner, Boucicault was careful not to show overt sympathy for the cause of Irish rebellion, and instead made his own character, loveable scamp Conn the Shaughraun, the focal point of the play. Boucicault continued to portray the youthful Conn well into his sixties, as audiences still clamored for his signature performance. Irish-Americans were thrilled with Boucicault, and he was presented with a prestigious award by community leaders in March 1875 “in recognition of the services he has rendered to the Irish people in elevating the stage representation of their character.” [5] Interestingly, to promote both his Irish patriotism and his own play, Boucicault wrote a letter to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli in 1876, entreating him to release all remaining Fenian prisoners.[6] Not only is “The Shaughraun” Boucicault’s most celebrated play, but it has a very special place in USF Libraries as well: digitized here is the prompt book for the very first performance of the play at Wallack’s Theatre in New York, with Boucicault’s handwritten plea for its preservation.

Boucicault was never able to replicate the achievements of his first three Irish plays, however, and “The Shaughraun” turned out to be his last major success. Yet Boucicault continued to produce Irish dramas that featured the same formula of Irish charm, patriotic undertones, and sensation scenes; unfortunately for his ego, his bank account, and his legacy, this formula had grown stale with audiences. Despite their lack of critical success, some of the ‘minor’ Irish plays produced in the 1880s have much to offer the historian and scholar of the theater. “The Amadan,” for example, utilizes current events in Ireland like landlord evictions and the Phoenix Park murders of 1882 as a backdrop, while “Cushla Machree” takes Sir Walter Scott’s Guy Mannering and transports it from the Scottish Highlands to the north of Ireland. These plays are found in USF’s Special Collections and contain numerous rewrites and major revisions in Boucicault’s own hand, demonstrating that he did all he could to generate another blockbuster Irish play before his eventual death in 1890.

Boucicault was never able to replicate the achievements of his first three Irish plays, however, and “The Shaughraun” turned out to be his last major success. Yet Boucicault continued to produce Irish dramas that featured the same formula of Irish charm, patriotic undertones, and sensation scenes; unfortunately for his ego, his bank account, and his legacy, this formula had grown stale with audiences. Despite their lack of critical success, some of the ‘minor’ Irish plays produced in the 1880s have much to offer the historian and scholar of the theater. “The Amadan,” for example, utilizes current events in Ireland like landlord evictions and the Phoenix Park murders of 1882 as a backdrop, while “Cushla Machree” takes Sir Walter Scott’s Guy Mannering and transports it from the Scottish Highlands to the north of Ireland. These plays are found in USF’s Special Collections and contain numerous rewrites and major revisions in Boucicault’s own hand, demonstrating that he did all he could to generate another blockbuster Irish play before his eventual death in 1890.

March 2023 seems an excellent time to reflect on the Irish plays of Dion Boucicault, and especially to appreciate his attempts to banish the stage Irishman and elevate the status of Irish people worldwide. Whether he succeeded or not is a question for another day, but perhaps we can think about what it truly means to be Irish this year, and forgo the green beer for a Guinness instead—all while enjoying the materials digitized here by the USF Libraries.

REFERENCES

[1] For illustrative examples, see L. Perry Curtis, Apes and Angels: The Irishman in Victorian Caricature, Rev. ed. Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997.

[2] For the definitive study, see Kerby A. Miller, Emigrants and Exiles. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

[3] Irish-American, Vol. 25, No. 3, 18 January 1873, 8.

[4] See David Krause, The Dolmen Boucicault. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1964, for a study of his three most famous Irish plays, “The Colleen Bawn,” “Arrah-na-Pogue,” and “The Shaughraun.” More recently, Deirdre McFeely has published the definitive study of Boucicault’s Irish plays: Deirdre McFeely, Dion Boucicault : Irish Identity on Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

[5] New York Herald, 7 March 1875, 5.

[6] New York Herald, 17 January 1876, 5. The request was ignored. Unbeknownst to Boucicault, the whaling ship Catalpa was already on its way to free these men from Freemantle prison in Western Australia. This dramatic rescue was planned by Irish-American nationalist leaders John Devoy and John Boyle O’Reilly, and you can still see the rescued prisoners on bottles of 19 Crimes wine today!