|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Jackson Rooming House was once a haven for black entertainers, athletes, teachers, clergymen, and visitors to Tampa, Florida. Located a block west of Tampa Union Station along Nebraska Avenue at 835 Zack Street — currently 851 East Zack St. — it is just a short walk east of the once-thriving Central Avenue business and entertainment district that was prominent during the era of Jim Crow racial segregation.

The Jackson House had humble beginnings. In 1906, Moses Jackson, a carpenter and trolley “section hand” who worked on the construction of Tampa Union Station, purchased the home from Frank James, a black laborer who had built the foundation as a small cottage by 1905. Moses Jackson married Sarah Allen, a young local laundress, in June 1908, and together they started a family in the house.

In May 1912, Tampa Union Station opened. Recognizing the house’s close proximity to the station, the Jackson family began accommodating African American visitors and porters on their porch — often allowing them to stay overnight on pallets to catch a train the following morning. Pairing a community need with a business opportunity, Moses and Sarah began the Jackson Rooming House in 1912, expanding the house from a small family cottage into a two-story, 24-bedroom, two-bathroom boarding facility by 1915.

Around this time, the Jackson family began other business ventures as well. Willie Robinson Jr., the grandson of Sarah Jackson, describes his grandmother as a “go-getter,” operating three small businesses simultaneously. In addition to running the Jackson House with her four daughters, Ora Dee, Josephine, Alberta, and Sarah (junior), (Moses was working outside of the rooming house), Sarah also operated a laundry service out of their backyard for local white judges and lawyers who practiced at the nearby wooden Hillsborough County Courthouse, on Franklin and Lafayette Streets.

By the 1930s, Sarah had started the first black-owned cab company in Tampa with her sons Earnest Jackson and Willie Hitchens, operating a cab stand near Central Hotel. With close access to Tampa Union Station, the Jackson brothers would pick up and drive Black visitors around the city — since other cab services and hotels at the time were for whites only. After many lucrative years in service under the names “Speedup” and “Economy Cab Companies,” the taxi service was eventually sold to a local Central Avenue entrepreneur and fireman, Mr. Wade of Wade Cabs, following an encounter in which a Ku Klux Klan member threatened Sarah and her children on their porch to sell the company.

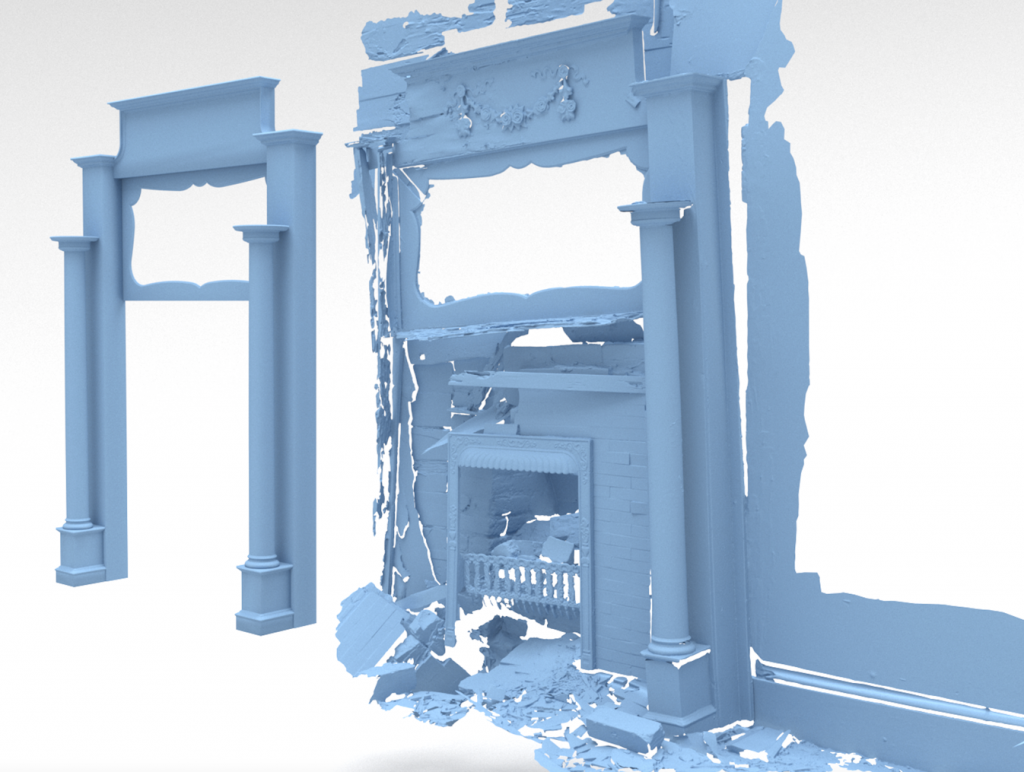

The Jackson House became a prominent business managed by the Jackson women during the era of segregation in Tampa throughout the mid 1900s. The younger Sarah Jackson (later married with the surname Robinson), remembers as a child in the 1920s and early 30s when guests would congregate in the parlor listening to guests/performers. The high ceilings made the house drafty, and so in winter, guests were supplied with quilts sewn by her mother. Three fireplaces heated the rooms throughout the house, due to lack of central heat, until after 1937. During those early years in the 1920s, guests mostly used kerosene lamps, as Moses Jackson only allowed electric lights to be used for a couple of hours each night. At 9:00 p.m., he would walk down the hallways and urge guests to turn off the lights and switch to the kerosene lamps for the remainder of the evening. Guests bathed in a washroom outside the house in the backyard and received a homecooked meal — all for only 25 cents a night or 75 cents a week. The boarding house was also cleaned by Sarah and her daughters, allowing for even more interactions with the renowned visitors who stayed there.

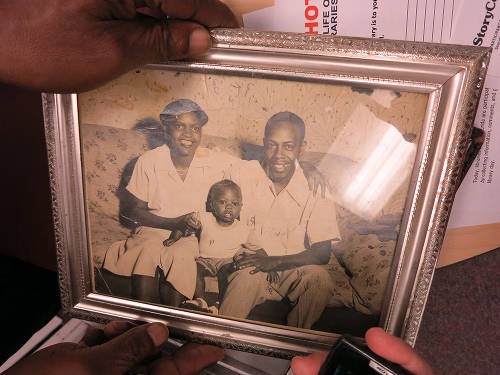

By the 1930s, the Jackson House had become a preferred accommodation for Black entertainers performing along Central Avenue. Before Moses Jackson passed away in 1929, a shed was added in the southwest corner of the lot to provide parking for travelers and entertainers passing through. In the 1930s and 40s, the extended Jackson family continued to live downstairs while guest rooms upstairs were booked at a rate of around two dollars per week. Sarah Jackson Robinson (right) remembers a young Ella Fitzgerald — while accompanying drummer Chick Webb and His Orchestra — writing her version of A-Tiskit, A-Taskit, “I Found My Yellow Basket” inside the living room of the Jackson House in 1938.

During World War II, returning Black G.I.s would stay at the boarding house while curfews were enforced in cities throughout the United States. By the mid-1940s into the 50s, the rhythm and blues and soul scene started bringing acts like Ray Charles, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, B.B. King, and James Brown to Tampa’s Central Avenue. During the heyday of the Jackson House, guests could play two pianos — one in the hallway and another in the living room — filling the first floor with music. Willie Robinson Jr. recounts that the Jackson House provided “5-star service” to guests — part of its enduring legacy and appeal to the famous clientele who passed through over the years.

After the family matriarch Sarah Jackson passed away in 1937, her daughters, Ora Dee, Josephine, and Sarah took turns managing the house. Sarah remembers a young James Brown coming to stay at the house while performing opening acts at clubs along Central Avenue with the band the Famous Flames. Over the years, she and her husband Willie Robinson, Sr. developed a closer relationship with James Brown over hair appointments at her husband’s barbershop, Marshall’s, when he came to town to perform.

While the Civil Rights Movement gained traction in Tampa during the 1950s and 60s, Sarah also began managing a beauty shop at 630 Nebraska Ave. She and her husband Willie continued living at the Jackson House with their son Willie Robinson Jr., along with extended family members, running the boarding house with more modern amenities. National Civil Rights activists and clergy met with Florida NAACP leaders like Robert Saunders, Sr. to promote the integration of Tampa, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was among the famed activists to stay at the Jackson House during this time.

By the late 1960s, African American patronage of facilities like the Jackson House began to decline with the dismantling of Jim Crow laws and norms following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965. Central Avenue was hit by urban renewal, which decimated Black-owned housing units and businesses for the expansion of Interstate-275 and other city developments. Days of civil unrest, arson, and looting following the murder of Martin Chambers, a young African American man shot by a white police officer in 1967, were said to contribute to the decline of the primarily Black-owned and operated business and entertainment district. Despite businesses closing around them, the Robinson family and Jackson House remained a part of the surrounding community. The family regularly attended Beulah Baptist Church a block and a half west of Central Avenue (604 E. Tyler Street) and would sometimes host parties for friends at the Rooming House.

Eventually, the Jackson House became the last surviving Black-owned business within the Central Avenue district and accommodated a limited number of guests until 1989. Sarah Robinson lived her entire life in the house until she passed away in 2006. She, her niece Johnnie Saunders, and her son Willie Robinson Jr. began efforts to preserve and restore the house as a historical landmark to honor their family’s legacy and Tampa’s Black heritage. Because of their efforts, the Jackson Rooming House became a part of the National Register of Historic Places in 2007. Willie Robinson Jr., Johnnie Saunders, and supporters continued the preservation campaign and eventually established the Jackson House Foundation nonprofit, chaired by Carolyn Collins, in 2014.

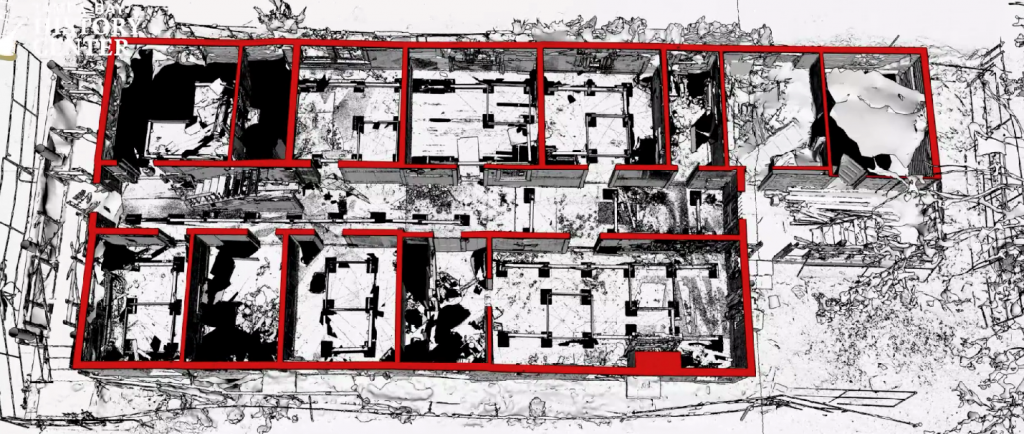

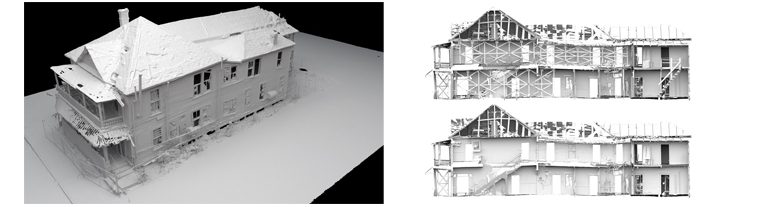

Today, surrounded by vacant lots and in a state of disrepair, the Foundation and its supporters have secured sufficient funding to begin restoration efforts with plans to transform the two-story, 4,000 square-foot home into a local Black history museum. Supported by the Vinik Family Foundation, the USF Libraries Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections (DHHC) are using the latest in high-tech imaging and surveying to work toward the long-term preservation of the structure. The DHHC’s survey also includes a comprehensive historical background and literature review, and a future USF Libraries collection will emerge bringing together archives such as oral histories, maps, and photographic collections. The team is also creating an online mapping tool that allows for the better understanding of Tampa through time, integrating these maps and photographic resources to show how the landscapes have changed or disappeared over time. These types of digital strategies will assist other project partners such as the Tampa Bay History Center, as they bring to life the story of the Jackson Rooming House, a time and place in Tampa’s past that holds significance to the public and future generations.

Take a look below to see behind-the-scenes (and walls) of the DHHC’s survey to save and preserve the Jackson House. The Tampa Bay History Center recently held a “Florida Conversation” online on Wednesday, February 17th at 6:30 p.m. about the preservation progress with History Center curators Dr. Brad Massey and Rodney Kite-Powell, along with local Historian Fred Hearns.