In 1971, a small-scale model of a Pablo Picasso sculpture, “Bust of a Woman,” was donated to the University of South Florida. Fifty years later, it received new attention from researchers after it was spotted on a shelf in the Tampa Library in 2018. Afterwards, Special Collections staff dug into the sculpture’s history and the intriguing story behind the model resurfaced.

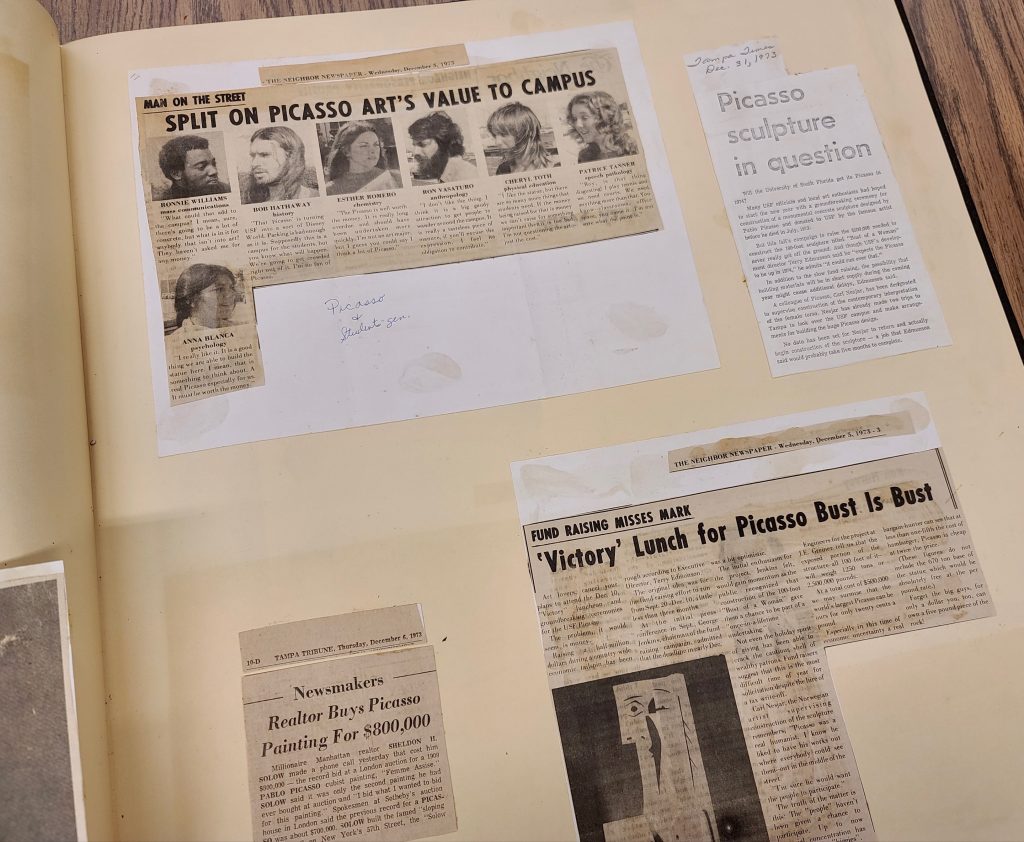

From the archives came audio reels, photographs, oral histories, a scrapbook, and numerous records[1] regarding the project and its fundraising. The model represented a proposed public art sculpture that was to be built on the University of South Florida campus. At ten stories tall, or 102 ft, the sculpture would have been Pablo Picasso’s largest single work as well as one of the world’s tallest concrete sculptures.

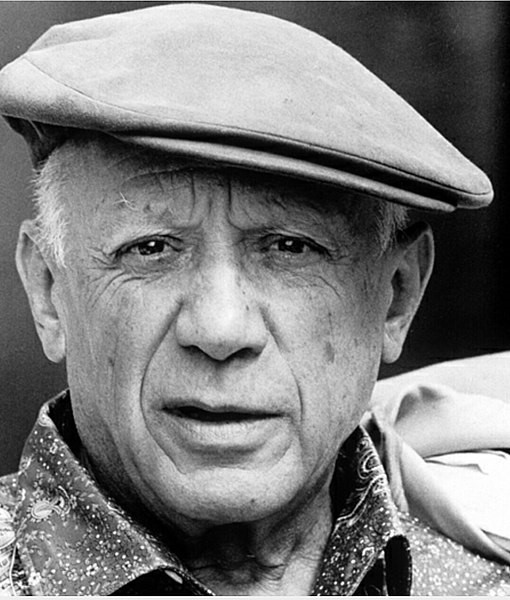

For nearly twenty years, Norwegian artist and sculptor, Carl Nesjar, was Picasso’s chosen fabricator, giving his drawings and models dimension and immense physical form. Picasso and Nesjar previously collaborated to create two works of public art on college campuses: “Bust of Sylvette” (1968) at New York University and “Head of a Woman” (1971) at Princeton University.[2] Nesjar would play a pivotal role in this project as well, while famous architect, Paul Rudolph, designed the accompanying art center.

Sadly, the monumental Pablo Picasso sculpture on the USF Tampa campus never came to be. The State Board of Regents approved the project on “April 9, 1973, a day after Picasso’s death, but did not agree to fund its estimated $10 million budget.”[3]

Want to learn more about this fascinating moment in USF history?

Read the recollections of Vincent Ahern, Coordinator of Public Art at the Institute for Research in Art, collected below:

In 1971, ’72, somewhere in that time frame, Pablo Picasso gave to the University of South Florida the rights to build one of his metal maquettes. A piece called Bust of a Woman. And he gave those rights to the university promising to take no fee, but with the stipulation that Carl Nesjar, a Norwegian sculptor who would introduce Picasso to a means by which large scale sculptures could be created utilizing cement. The stipulation was that Mr. Nesjar would have to supervise the construction of the piece. So, the university was very enthusiastic about the chance to build something that obviously would bring instant recognition, and planning as they were in that time frame, a major art center, decided to build a Picasso in conjunction with this arts center. I remember the date, 1972, ’73 and if you’re familiar with the history of the country at that point and time you realize we were experiencing a tremendous economic decline because of the gas crisis. People were in long lines waiting to get five dollars’ worth of gas, so on and so forth. And so, the economy suffered. Obviously, to build this project and to build the arts center would require that kind of generosity that I mentioned earlier, because at that point in time there was no art in state buildings funding. And so, the funds to build the project, which at that point in time amounted to about $500,000 had to be raised. We couldn’t raise the funds. We did however do a number of things in that time frame—the university did, that would eventually come to the surface in the early ’90s. One of the things we did was an engineering study done by Griner Engineering by an individual who was hired as an engineer at the time, James Sawyer. He went by the name Tom Sawyer, like the connection to the literature.

At any rate, they created a series of maquettes. They obviously engaged Carl Nesjar in the discussion, and they created an engineering study for this project that was to be at that point in time, they were going to build it at 102 feet. It would have been large enough to have been seen from interstate 275 and would have obviously been a dominant structure on campus. Couldn’t raise the money, didn’t build it, and the files were gathered and actually archived in the galleries that eventually would become the contemporary art museum.

In 1992, ’93, somewhere thereabouts, Dr. Frank Borkowski was president of the university at the time. I guess must have seen some of these old Oracles also because he approached Margaret Miller, and Margaret eventually myself with the possibility of re-investigating the building of the Picasso. And we did that. One of the first things I did was to read the old files and, again, get an understanding of the folks involved and saw the name Tom Sawyer. And so, I called Griner on the off chance that he was still employed there since he had so much early information, or information from the early effort, and he was. And he said, “Come on down.” You know, I thought I was going down to meet with an engineer and I ended up meeting with the president of the company, who never told me he was the president of the company, he just said, “Come on down.” And anyway, he was very enthusiastic and agreed to support again the project and provide certain in-kind gifts, but we still were going to need significant funds. We also would need Carl Nesjar involved. So, we contacted him, Carl, as I mentioned, lives in Norway, and we invited him to come to the campus and work with us in terms of what it would take and where it might be sited and so on. So, we ended up doing a study that sighted the project adjacent to the Lifsey house, the president’s home, that was under design and development at that point and time. And then we still, obviously had the biggest hurdle to overcome, which, again, was funding. And so Margaret Millet led a group that went to Spain to talk with a number of foundations, obviously Picasso having been born in Spain is honored there in a number of ways, including foundations to support the use of his work and images. The visit was made and we had the possibility of some funding but we were looking at 1.5 million dollars. At this point in time, my research had continued. One of the folks that I talked to was William Ruben, who had been the director of the Museum of Modern Art and shown the maquette for our bust back in the ’60s. And I asked for his input and he actually discouraged us. He said, “You know, Picasso—”at this point in time, Picasso died in the mid ’70s. Had been dead for, obviously, a number of years and to build a project that many years after his death might not be something that would end up garnering an awful lot of respect. Even though Picasso gave us the right, and even though Nesjar was still alive, he felt queasy about that idea and shared that sense of concern with me. Another even occurred in that same time frame. Claude Picasso, who’s Picasso’s son, now living in Paris, contacted the university and was asking for a fee if we were to decide to build this project. Now Pablo obviously didn’t ask for any money but his son wanted some sort of finances to exchange hands if we were going to build it. And asked us to cease and desist on any further efforts until those arrangements were made. The culmination of Claude Picasso’s request and the response from the art world, really in the form of William Ruben’s comments, plus the difficulty of raising those kinds of funds and the consequences of spending those kinds of funds, that’s an awful lot of money to spend on the arts. All three of those things came together to convince the president that we better not continue to pursue this project. And so, that’s the history of the Picasso as it stands today.

USF 50th (2006) Anniversary Oral History Project, “Vincent Ahern,” (U23-00002) p. 13-16, https://digital.lib.usf.edu/SFS0024312/00001

Discover more interesting, and sometimes curious, recollections housed in USF Digital Collections and USF Special Collections.

Want more USF Curiosities? Check out the posts in this series:

- USF Curiosities: Sand as far as the eye could see?

- USF Curiosities: An elephant on the roof?

- USF Curiosities: Chickens in the elevator?

- USF Curiosities: Bottle Cap U? Sandspur U?

- USF Curiosities: Planting trees at “Sandspur U”?

- USF Curiosities: The Golden Brahman?

- USF Curiosities: A faculty airplane?

- USF Curiosities: Chariot races?

- USF Curiosities: A 40-foot Band-Aid?

REFERENCES

[1] Archival documentation from USF Special Collections on this subject include: https://archives.lib.usf.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/108467, https://archives.lib.usf.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/102790, https://archives.lib.usf.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/87493, and https://archives.lib.usf.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/87494.

[2] Factual information in this paragraph was found on: Martin, Andrea. (2018). Discovered Recording Will Help Build Picasso Sculpture – Virtually. WUSF Public Media – WUSF 89.7 website. https://wusfnews.wusf.usf.edu/culture/2018-03-06/discovered-recording-will-help-build-picasso-sculpture-virtually.

[3] WUSF Public Media. (2018, March 18). Audio Recording About Picasso’s USF Sculpture , Discovered. WUSF Public Media website. https://wusfnews.wusf.usf.edu/news/2018-03-05/audio-recording-about-picassos-usf-sculpture-discovered