Post written by Lesley Brooks and Jane Duncan

For two centuries, nurses have been the picture of care, empathy, and compassion in healthcare. They see patients through vulnerable moments, difficult decisions, hardships, and moments of joy. Day in and day out, nurses uplift, support, and diligently care for their patients, providing a positive, compassionate presence to hospital rooms, doctor’s offices, care facilities, and treatment centers.

In celebration of their tremendous efforts, Digital Dialogs is celebrating Nurses Week 2021 with a look at their personal experiences, as documented in two of USF Libraries’ oral history collections:

- The Florida Public Health Oral History Project

- The Otis R. Anthony African Americans in Florida Oral History Project

Learn more about the changing landscape of Florida public health by exploring the sections below.

Florida Public Health Oral History Project

Established in 1997, the Florida Public Health Oral History Project (1997-2002) documents the experiences of nurses, nurse midwives, physicians, administrators, laboratory managers, epidemiologists, and many other experts, prominent in Florida’s public health field.[1] Housing 63 oral histories, this collection explores each individual’s motivation to pursue a career in the field, their education, the challenges and highlights of their jobs, and their determination to ensure the health of Florida residents despite organizational upheaval and the vicissitudes of state politics.

Gertrude Lee, former Director of Public Health Nursing in Holmes County, describes nursing in rural communities in the 1940s:

“Dirt roads—slick roads and sandy roads. You were either on one or the other. You were on a clay road that was as slick as a button, and especially if it had rained, or you were on sand, where you bogged down in it … Well, there usually was somebody that would come along, or else there would be a farmer close by that had a pair of mules that would come and drag me out. I would get out and walk to the house and tell him I was stuck. That was a marvelous thing, back doing public health nursing back then … way back, whenever we were doing public health nursing, the people were proud of their public health nurses. And I said that I take it from the standpoint they had ownership of their county health department … And they felt the ownership of their county health departments. And they protected not only the nurse but the sanitation officer as well and all of that sort of thing back in those days. You were not afraid to go anywhere that you needed to go because you just were not afraid to go because you were a special person back then. And maybe that’s the reason I stayed in public health, I wanted to be a special person.”

— Gertrude Lee, Florida Public Health Oral History Project (C53-00044, p.12 )

Alma Vause, a former nurse midwife, recalls the compassion she felt for her patients and how she ensured patients were supported and comforted, even in their final moments:

“You know, I look back, and I see some of the things that I’ve done, and I feel good about them. Right now, when I was in, my highlight when I was in the school of nursing … when you got off duty, you could do some things if you got permission. And there were some people on the medical ward that were sick, and they liked to—never would come in until they were ready to pass away. And the family would come, and they couldn’t look at them … And I would, when I got off duty, if this nursing director or the person on the floor would give me permission, I would come back and sit with those people, with the patients, so they wouldn’t be by themselves.

And I think the thing that helped me at that time the most, there were several people that I sat with as they passed. I even did that here in Winter Haven with a family member, that they couldn’t do it. Now, that, even today I would do it because I hate for a person to feel like they’re alone when they’re passing from one life to another.”

—Alma Vause, Florida Public Health Oral History Project (C53-00035, p. 30)

Otis R. Anthony African Americans in Florida Oral History Project

The Otis R. Anthony African Americans in Florida Oral History Project (1977-1979, 1993-2009) was established by the Tampa Urban League and the Hillsborough County Museum. Under the direction of community activist Otis R. Anthony as part of the Black History of Tampa Project, oral history interviews were conducted to record the personal experiences of African Americans in Florida. The majority of these interviews took place between 1977 and 1978. Additional interviews were conducted by the USF Department of Anthropology after the collection was donated to them by Anthony in 1994 to support their Central Avenue Legacies Project. These interviews focus primarily on Central Avenue and the Afro-Cuban community. Now comprising 83 oral histories, this collection helps to document the changing picture of public health in Florida.

In their interviews, Doris Reddick and Flora Williams speak about how segregation and later racial integration effected nursing and public health. While a few quotations are available below, extended discussions of their experiences as nurses are available by clicking their names under each quotation.

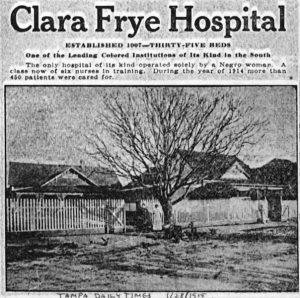

Doris Reddick began working at Clara Frye Hospital as a nurse in 1936. At the time, “the[re] were only two black hospitals in Hillsborough county” (7). Clare Frye Hospital was founded in 1907 with thirty-five beds. By 1914, more than 450 patients were being seen annually [2]. When Flora Williams came to Clare Frye in 1938, she found “the conditions at that time were deplorable, because it was just an old house—not really built for a hospital, but sort of a makeshift thing that they used as a hospital” (1).

In 1961, Doris Reddick began working at the Health Department. She remembers the moment that things began to change there:

“I worked there in many capacities. I worked as general—more or less what you would classify as a general duty nurse. And then from there it was staff advisor, you know, and whatnot like this. I was in charge of the clinics and different things that. I was there as the clinic began to change. That was Neimanus’ first year when I was there, and he was the one who took the signs off the doors saying this is White and this Black, and you couldn’t do this and that and the other. But he was the one who did it, and it was going through change when I first went there. And it was becoming totally integrated at this particular time. And it was a pleasant place to work, and the people were nice and all this, and we became totally integrated.”

— Doris Reddick, Otis R. Anthony African Americans in Florida Oral History Project (A31-00043, p. 4)

As a visiting public health nurse, Flora Williams remembers:

“During the earlier years, before 1965, blacks only made home visits to blacks; whites made home visits to whites. After then, everybody made home visits to everybody … And each nurse made home visits, a certain amount of home visits each and every day, five days a week, and she made those—if she wasn’t in a clinic. The day she was in a clinic, she couldn’t get out and make a whole lot of visits, but if she was in a clinic in the morning, she made visits in the afternoon. If she was in the clinic in the afternoon, she made visits in the morning, unless she had a lot of desk work to do. And desk work to do is, I mean, catching up on, say, records and filing and so on and so forth, like that. But the nurses after sixty-five [1965], all the nurses made visits on everybody. And it was a sort of delightful thing, because it was new, it was different, and we sort of enjoyed it. And then we all became what you call a VNA [Visiting Nursing Association] nursing, visiting nursing, as well as public health nursing.”

— Flora Williams, Otis R. Anthony African Americans in Florida Oral History Project (A31-00076, p. 8)

Additional Resources

Learn more about the history of nursing by reading our Nurses Week 2020 article:

Browse our oral history collections:

- — Florida Public Health Oral History Project

- — Otis R. Anthony African Americans in Florida Oral History Project

Explore more nursing-related digital collections:

- — Gordon Keller School of Nursing Alumnae Association Records

- — A selection of digitized items from the Robertson and Fresh Collection of Tampa Photographs

REFERENCES

[2] Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education. (2002). Clara Frye Hospital. Exploring Florida: A Social Studies Resource for Students and Teachers. http://fcit.usf.edu/FLORIDA/photos/gov/health/0369.htm.

Lee, Gertrude. (1999, September 8). Gertrude Lee, Interview by E. Charlton Prather [Transcript]. Florida Public Health Oral History Project (C53-00044). USF Digital Collections, Tampa, FL. p. 12. https://digital.lib.usf.edu/?c53.44.

Reddick, Doris. (1978, August 14). Flora Williams, Interview by Otis Anthony [Transcript]. Otis R. Anthony African Americans in Florida Oral History Project (A31-00043). USF Digital Collections, Tampa, FL. p. 4, 7. https://digital.lib.usf.edu/?a31.43.

Vause, Alma. (1997, September 9). Alma Vause, Interview by E. Charlton Prather [Transcript]. Florida Public Health Oral History Project (C53-00035). USF Digital Collections, Tampa, FL. p. 30. https://digital.lib.usf.edu/?c53.35.

Williams, Flora. (1978, August 13). Flora Williams, Interview by Otis Anthony [Transcript]. Otis R. Anthony African Americans in Florida Oral History Project (A31-00076). USF Digital Collections, Tampa, FL. p. 1, 8. https://digital.lib.usf.edu/?a31.76.

NOTES

[1] The Florida Public Health Oral History Project was established by Dr. Charles Mahan (dean of the USF College of Public Health), Sam Fustukjian (director of the USF Libraries), and Dr. E. Charlton Prather (a former Florida health officer). The interviews were conducted at Florida Department of Health units in Tallahassee, Jacksonville, and West Palm Beach from 1997-2002.