A Space for Students

Supporting Students at the Library

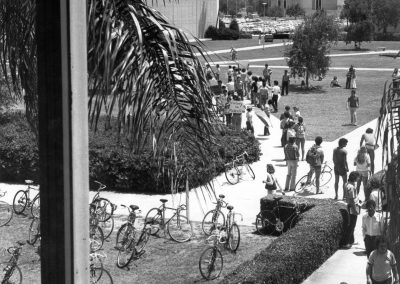

Providing support to students and faculty has always been the library’s first priority, but the job was not always as simple as it sounds. Among all the changes in campus construction and technology, perhaps the richest subject in the history of the library is the students themselves. In addition to its intellectual role, the library served as an early social hub on campus. It served as an ideal neutral meeting place for student studies, especially since it was located next to the University Center, now the Marshall Student Center, which contained the only eatery on campus back then. The patio became a favorite for couples, leading to a tradition of “patio dates.” The patio’s pond was a favorite target of pranksters, who regularly polluted the pool with dye, soap, shark repellant, and ink, and local wildlife sometimes found their way in for a swim.

As a touchstone for student life, the library became part of USF’s political landscape. The first open protests occurred around the unofficial dress code, which mandated long pants and dresses for students on the sunbeaten campus. Students rallied against the administration’s habit of canceling lectures on sensitive subjects, from leftist politics to college football. In the late 1960s, it was not unusual for students to march in support of professors who ran afoul of the administration.

Race relations took center stage in 1969-70, when matters came to a head at USF. African American students in militant garb marched on campus demanding an Afro Studies department, their own lounge, and more library materials pertinent to the black experience. Students formed a group called “Students for a Non-Racist Library,” accusing library officials of “breaking promises” for more materials on black themes. Just days later, library staff shelved a rush order to fulfill the need.

USF had its share of protests against the Vietnam War. Only once did the library seem threatened, an incident Harkness recalls in detail:

“One particular time when there was an all-night [student protest] session and I know I was a little concerned about closing – there were libraries at other places that were trashed and things like that. [I] prepared to spend the night at the library if need be[.] It was closed very quietly. The students, the activists were not interested in demonstrating in the library. They were mostly interested in sitting around and smoking pot and singing and there were a few speeches.”

During the 1970s, some students, oblivious to politics and all else, stumbled from the Empty Keg (the student rathskeller) across the street to sleep off drinks in the library’s lobby on Friday nights. Walter Rowe, then working as a security guard, remembered, “We’d have to kick their feet to get them to wake up when we closed out. There was one guy [who] walked out the front door who literally laid down on the sidewalk and went right back to sleep. I had to move him so I could get around to lock the door.”

Protecting library property was a distinct challenge. Library staff and faculty were rightly concerned with the security of the materials, but help was on the way. One of the second library’s most attractive features proved to be “TattleTape,” an electronic system that tallied patrons at the entrance and provided collections security at the exit. “Some lenders want an arm and leg for security,” a promotional sign read. “Your library just wants the book back.” Security guards would no longer be necessary to check bags. Paul Camp had the honor of being the first to set off the untested security system in the midst of the move. “I had my book I was reading at lunch and I hadn’t checked it out. I come ambling along, and all of a sudden, I hit the gate and it locks and it goes ‘Bing!’”

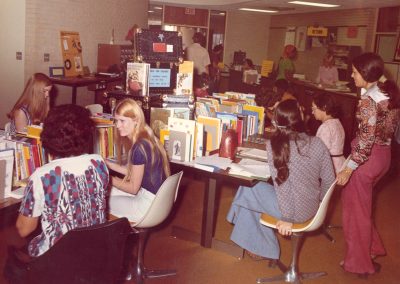

Aside from the occasional protest, the library’s relationship with students was far more collegial. The Graduate Assistant program began in tandem with the Library Science program in 1976, with more than two hundred alumni. The program was originally used to provide student instructors to work with reference librarians for a course The Use of the Library (Silver & Cunningham, 2008). The successful program was discontinued amid disagreements over funding in the 2010s.

The Graduate Assistant program discontinuation didn’t end the library’s relationship with students. Several departments offered opportunities for students to work on campus and obtain experience in the library. By 2012 a new reference desk and training program was launched to elevate the visibility of research assistance on the first floor. This desk would be staffed primarily by specially trained student assistants (Todorinova & Torrence, 2013).

References

Silver, S., & Cunningham, V. (2008). The Impact of the USF Tampa Library Graduate Assistant Program on Career and Professional Development. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED500319.pdf

Todorinova, L., & Torrence, M. (2013). Implementing and Assessing Library Reference Training Programs. The Reference Librarian, 55(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2014.853277