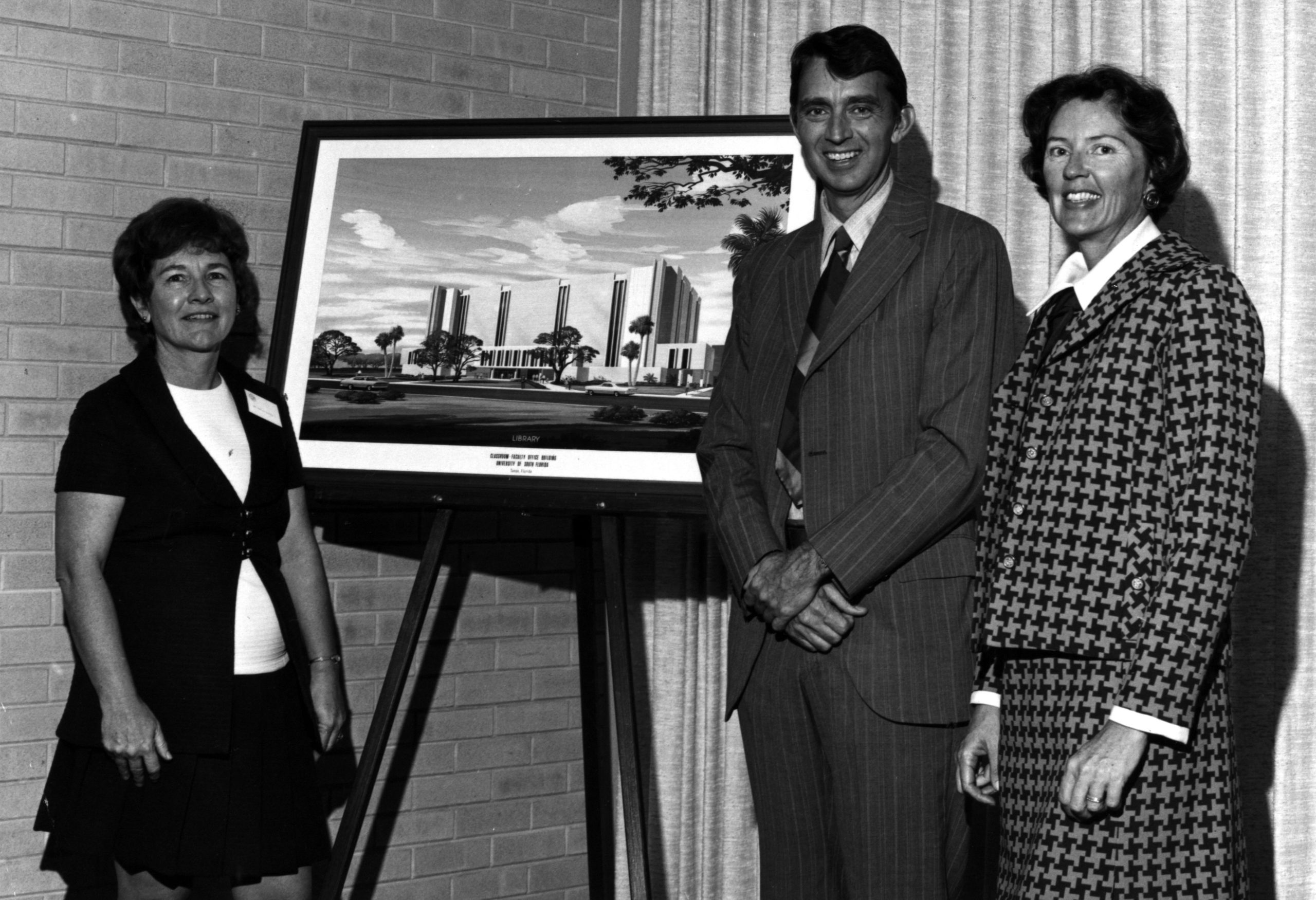

The “New” Library (1975)

Opening of the Current Library

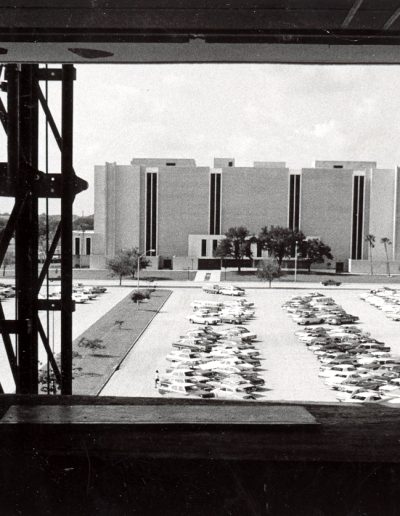

The new building was impressive, and opened in time for fall session on September 15, 1975. “Many of us were convinced that we would never find our way around the building,” Vastine recalls, “it was so big compared to what we were used to. Even the faculty was concerned about finding their way out.” Some could not find their way out of the new elevators, which constantly broke down. No air conditioning reached the top two floors until a helicopter airlifted a unit to the roof. Trendy decorators decked out the library in 70s colors: with the carpet aligned with the color-coded stacks. “It looked good at first,” Vastine relates, “but it didn’t age well.” Harrison Covington, the former Dean of the College of Fine Arts, won the contest to supply the new building with a piece of original art. With a central figure based upon Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch “Proportions of Man,” the sculpture depicts the transfer of knowledge over generations.

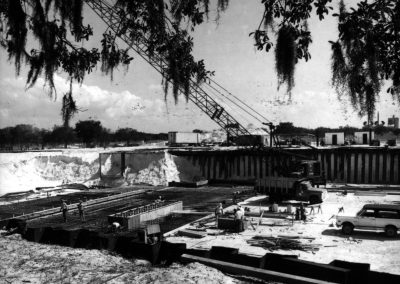

“It was built with special care because the dirt was excavated. The hole was filled with what they call grout, I guess, and was vibrated and then a grid was put over it, more concrete poured, vibrated, finally they put on that hole the weight of the building and the books so that the library was well built, sturdily built, and was really the most important building on campus. And, the librarian was the first appointment.” – Grace Allen

Students came back in droves to study and converse. “By the time we moved,” Harkness said, “we were serving twenty thousand students and had about four hundred and fifty thousand volumes. Now that shows, I think, how rapidly both University enrollment grew and the University library grew.” The influential anthropologist Margaret Mead attended the dedication of the new library on March 6, 1976. When students tried to disrupt her speech with protests, she shut them down, saying it was not the time or place.

President John Lott Brown, exasperated by the high cost of running an academic library, searched for unorthodox solutions in the 1980s. “We’re running out of space and the cost is just too high (to run conventional libraries).” Brown proposed a gradual transition to electronic storage of information, beginning with increased microfiche storage. He also proposed that the microfiche readers may eventually be “replaced by electronic systems capable of scanning the page of a book in a fraction of a second.” According to the Oracle, by 1992, students might be able to “turn to the University-loaned computer terminal in his or her room, phone the information center to request the journal and – Presto! the journal appears on the computer screen.” The library began to convert some major journals to microfiche, in part to modernize, but mostly for protection.

The St. Petersburg campus completed the attractive Nelson Poynter Library in 1981, named after the publisher of the St. Petersburg Times. The fledgling Sarasota campus gained a library in 1985, as did New College in 1986 (which was under USF’s administration from 1975 to 2001).

Pests and Disasters

A plague of insects prompted the purchase of a $9,000 machine to root them out in the late 1970s, but one of the library’s worst disasters took place in 1980, Rowe recalls. The building’s air conditioning was shut down over a hot summer weekend. By Monday, white mold covered many of the books. “We tried to wipe them down the best we could [using] an alcohol solution, which now is really against the rules. If we were shelving, we were wiping. We had people who would not go to the 5th floor” because of their sensitivity to the outbreak. Rowe commented that the 5th floor was not quite right for about twenty years after. In 1985, mildew became the latest physical crisis, with fans running on all floors.

Other parts of the library never seemed quite right, the elevators being one of them. After two students free-fell one story in an elevator, thudding on the basement below, library employees reacted with no excitement to the rattled students: “It slips all the time.” “We’re not indifferent to the problem,” explained Library Director Mary Lou Harkness, “we have continuing minor problems with the elevators.”