Species Account

The Rose-ringed Parakeet is endemic to 2 discontinuous areas of Africa and Asia. In Africa, African Rose-ringed Parakeet (P. k. krameri) and Abyssinian Rose-ringed Parakeet (P. k. parvirostris) range coast to coast between the Sahara Desert to the north and the tropical rain forest ecoregion to the south; the larger Boreal Rose-ringed Parakeet (P. k. borealis) and Indian Rose-ringed Parakeet (P. k. manillensis) are native to Southern Asia, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar (Forshaw 2010, Strubbe and Matthysen 2020). Considered by some to be the most invasive nonnative psittacine in the world and a destructive agricultural pest, this popular caged bird now breeds in 35 countries in every continent except Australia and Antarctica (Jackson 2021).

Despite the species’ reputation for aggressively out-competing native birds, its numbers have remained low since its introduction in Florida between the 1930s (Edscorn 1977) and 1960s (Owre 1973). Breeding has been confirmed in Citrus, Miami-Dade, Pinellas, and Collier counties, with occasional sightings of lone escapees and possible breeding pairs across the state as far north as St. Johns County (Neville 2003). Rose-ringed Parakeets are secondary cavity nesters that accept or modify holes in trees, utility poles (Neville 2003), or walls where young remain for 6 to 7 weeks before fledging (Forshaw 1973).

Citation: Dellinger, R. L. 2024. Rose-ringed Parakeet (Psittacula krameri). In A. B. Hodgson, editor. Florida Breeding Bird Atlas II. Special Publication Number 9. Florida Ornithological Society, Tampa, USA.

Banner Photograph: Susan Young

Close Up Image: Carole Devillers

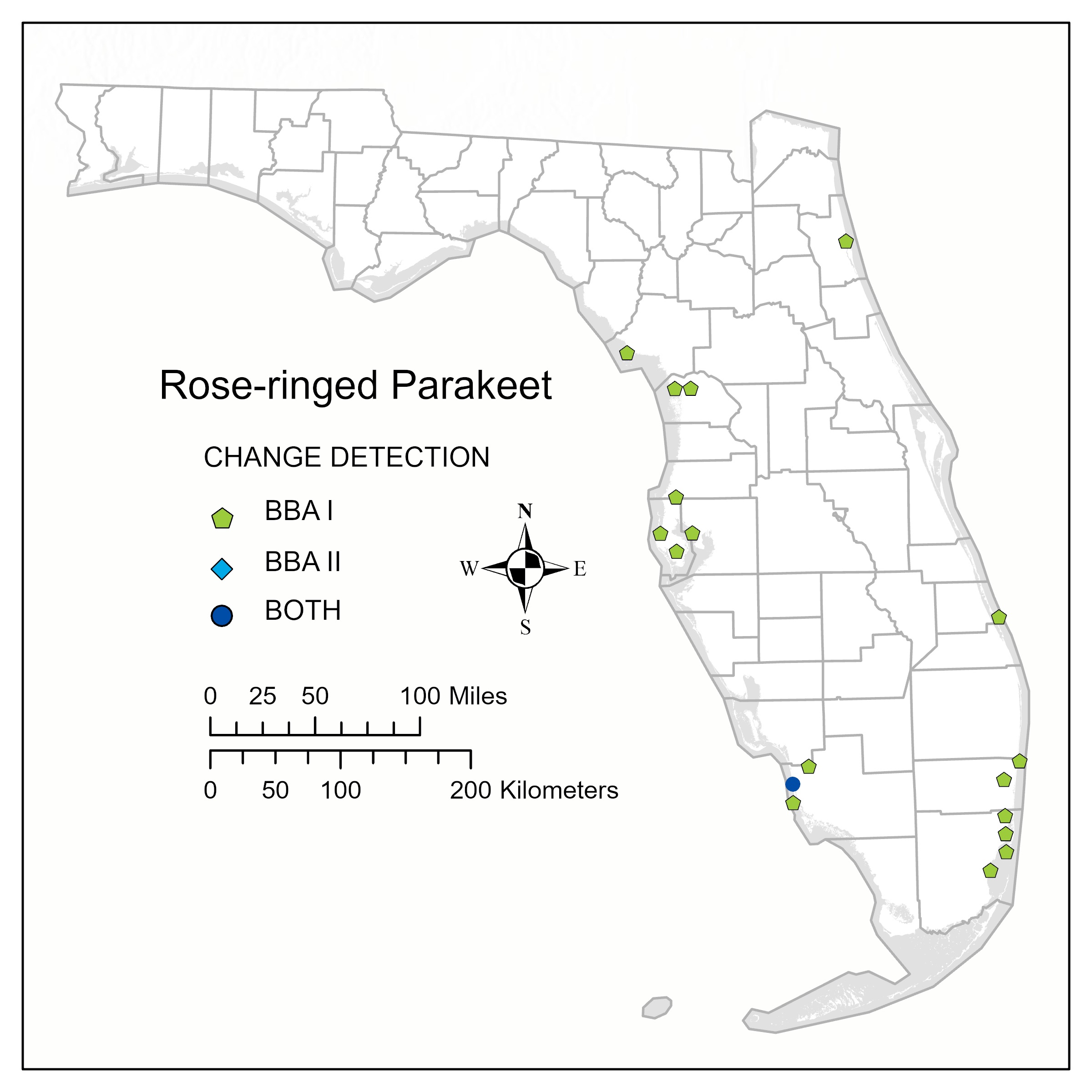

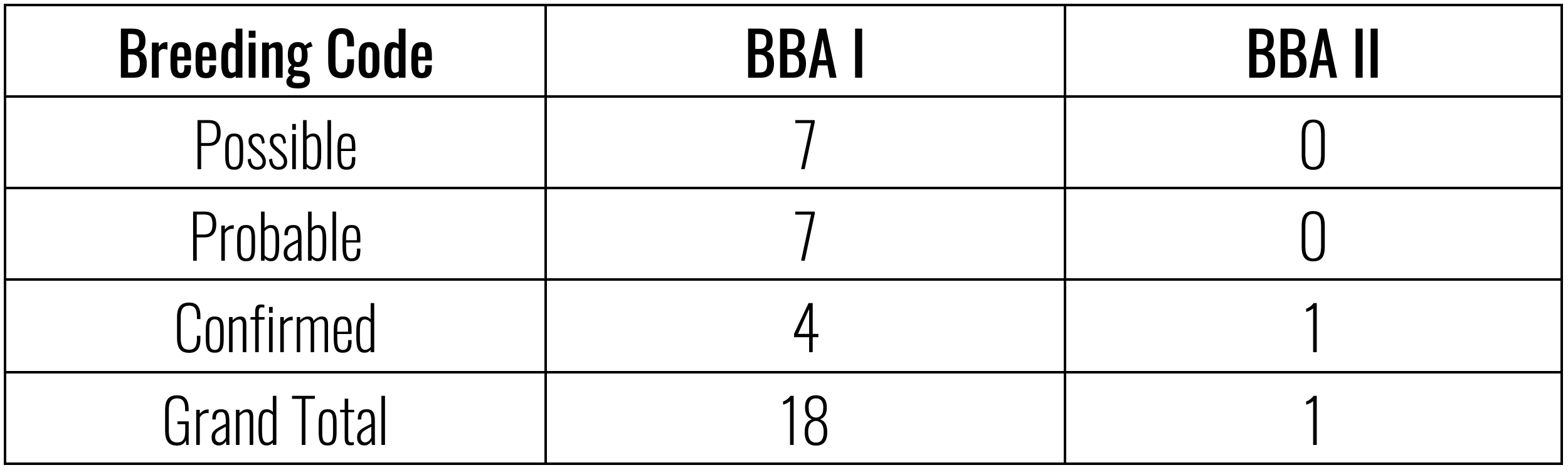

Updated Status. Atlasers confirmed Rose-ringed Parakeets breeding in more quads during BBA I than in BBA II; 7 additional observations of possible, 7 of probable, and 3 of confirmed breeding records were made during BBA I (Table 1).

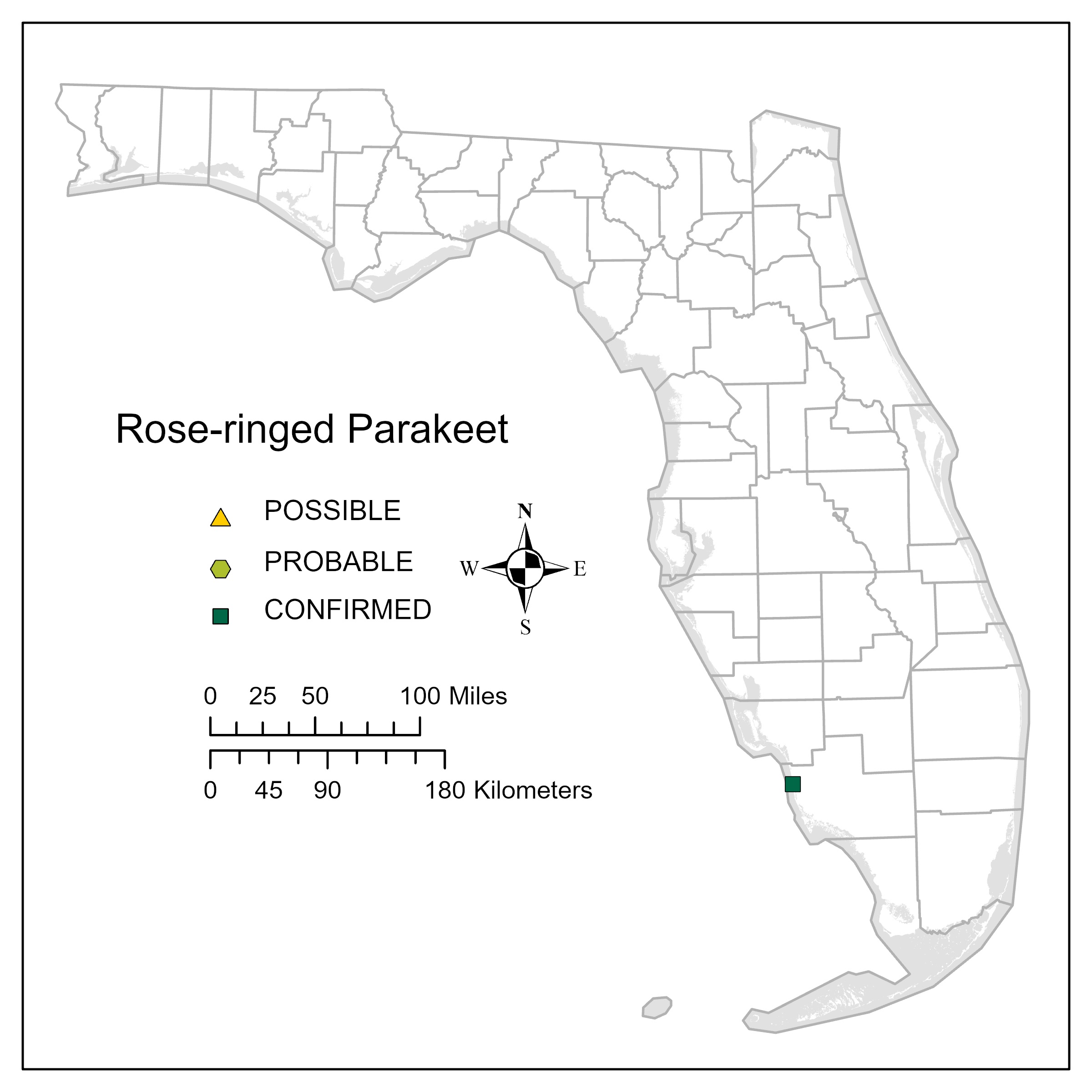

Rose-ringed Parakeets were only sighted once during BBA II surveys, resulting in no change to its confirmed breeding status (Figure 1). However, a comparison of BBA I and BBA II maps suggests a dramatic decrease in the species’ distribution since BBA I (Figure 2). This apparent decline, however, may be better explained by apparent reduced effort of atlasers in areas where the parakeets normally occur. Of counties where parakeets were confirmed breeding during BBA I, Citrus and Pinellas atlasers reported only 85-95% of total species observed during BBA I, and Collier and Miami-Dade atlasers only 75-85%. Thus, atlasers may not have searched all quads equally. Additionally, Rose-ringed Parakeets may fly up to 12 miles daily between breeding, foraging, and roosting areas (Keijl 2001, Kahl-Dunkel and Werner 2002), a characteristic that increases their likelihood of being overlooked by atlasers.

Whether BBA II data are a product of reduced atlasing effort or reflect a true decline in individuals, the few observations nevertheless underscore that Rose-ringed Parakeets are not as pestiferous in Florida as seen in Europe, where they are listed among the top 100 worst exotic species (Roy et al. 2020). The difference may be attributable to the fact that the manillensis subspecies naturally occurs at latitudes south of 20°N and, thus, may be at a climatological disadvantage for breeding in Florida (Jackson et al. 2015). In contrast, introduced European populations include Boreal Rose-ringed Parakeet, which is from a slightly more northern region (Morgan 1993). Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) estimated trends are not included for Rose-ringed Parakeets.

Data

Table 1

Maps

Figure 1

Figure 1. Rose-ringed Parakeet quad-level distribution, Florida Breeding Bird Atlas II. Figures 1 and 2 are based on data collected across all six atlas blocks within a quad. Figure 1 is based on the highest breeding code observed in each quad.

References

Edscorn, J. 1977. Florida birds. Florida Naturalist 50:30.

Forshaw, J. 1973. Parrots of the world. Lansdowne, Manchester, UK.

Jackson, H. 2021. Global invasion success of the rose-ringed parakeet. Pages 159-172 in S. Pruett-Jones, editor. Naturalized parrots of the world. Princeton University Press, New Jersey, USA.

Jackson, H., D. Strubbe, S. Tollington, R. Prys-Jones, E. Matthysen, and J. J. Groombridge. 2015. Ancestral origins and invasion pathways in a globally invasive bird correlate with climate and influences from bird trade. Molecular Ecology 24:4269-4285. DOI:10.1111/mec.13307.

Kahl-Dunkel, A, and R. Werner. 2002. Winter distribution of the ring-necked parakeet Psittacula krameri in Cologne. Vogelwelt 123:17-20 [German].

Keijl, G. 2001. Ring-necked parakeets Psittacula krameri in Amsterdam 1976-2000. Limosa 74:29-33.

Morgan, D. H. 1993. Feral rose-ringed parakeets in Britain. British Birds 86:561-564.

Neville, B. 2003. Rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameria). In Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, editor. Florida’s breeding bird atlas: A collaborative study of Florida’s birdlife. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tallahassee, USA. https://myfwc.com/media/19779/bba_rrpa.pdf.

Owre, T. 1973. A consideration of the exotic avifauna of southeastern Florida. Wilson Bulletin 85:491-500.

Roy, D., D. Alderman, P. Anastasiu, M. Arianoutsou, S. Augustin, S. Bacher, C. Basnou, J. Beisel, S. Bertolino, L. Bonesi, et al. 2020. DAISIE – Inventory of alien invasive species in Europe. Version 1.7. Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO). Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/ybwd3x. Accessed 12 June 2022.

Strubb, D. and E. Matthysen. 2020. Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri Scopoli, 1796). Pages 69-75 in C. T. Downs and L. A. Hart, editors. Invasive birds: global trends and impacts. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.