Species Account

The Limpkin is an iconic Florida wading bird known for its specialized foraging on the native Florida apple snail (Pomacea paludosa) (Bryan 2020). However, since the 1990s, the Limpkin has benefited from the rapid population growth and spread of the non-native island (giant) apple snail (Pomacea maculata; synonym P. insularum) (Benson 2022). The island apple snail is native to South America but became established in Texas by 1989 and in Florida by the mid-1990s, and has now expanded into Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina (Rawlings et al. 2007, Benson 2022). It thrives in more types of wetlands, tolerates higher salinity, and survives in cooler latitudes than the Florida apple snail (Rawlings et al. 2007, Underwood et al. 2019).

The Limpkin readily eats island apple snails, and the Limpkin’s range, previously being largely restricted to Florida, has also expanded into the southeastern states, where it is now resident in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina (eBird 2021), and has been sighted in many other states. Breeding has been documented in Georgia (2016), Louisiana (2018), and South Carolina (2020) (Craig Watson, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, personal communication). The Limpkin’s range expansion outside of Florida is attributed both to newly available populations of island apple snails (Dobbs 2019) and also to vagrancy, as birds wander even further from the expanding Limpkin population.

Most Limpkin nesting in southern Florida occurs from early February through May and in central and northern Florida from late February through June, with double-clutching common (Bryan 2003, 2020).

Citation: Bryan, D. C. 2023. Limpkin (Aramus guarauna). Pages 279-283 in A. B. Hodgson, editor. Florida Breeding Bird Atlas II. Special Publication Number 9. Florida Ornithological Society, Tampa, USA.

Banner Photograph: Dana Bryan

Illustration: Diane Pierce

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Updated Status

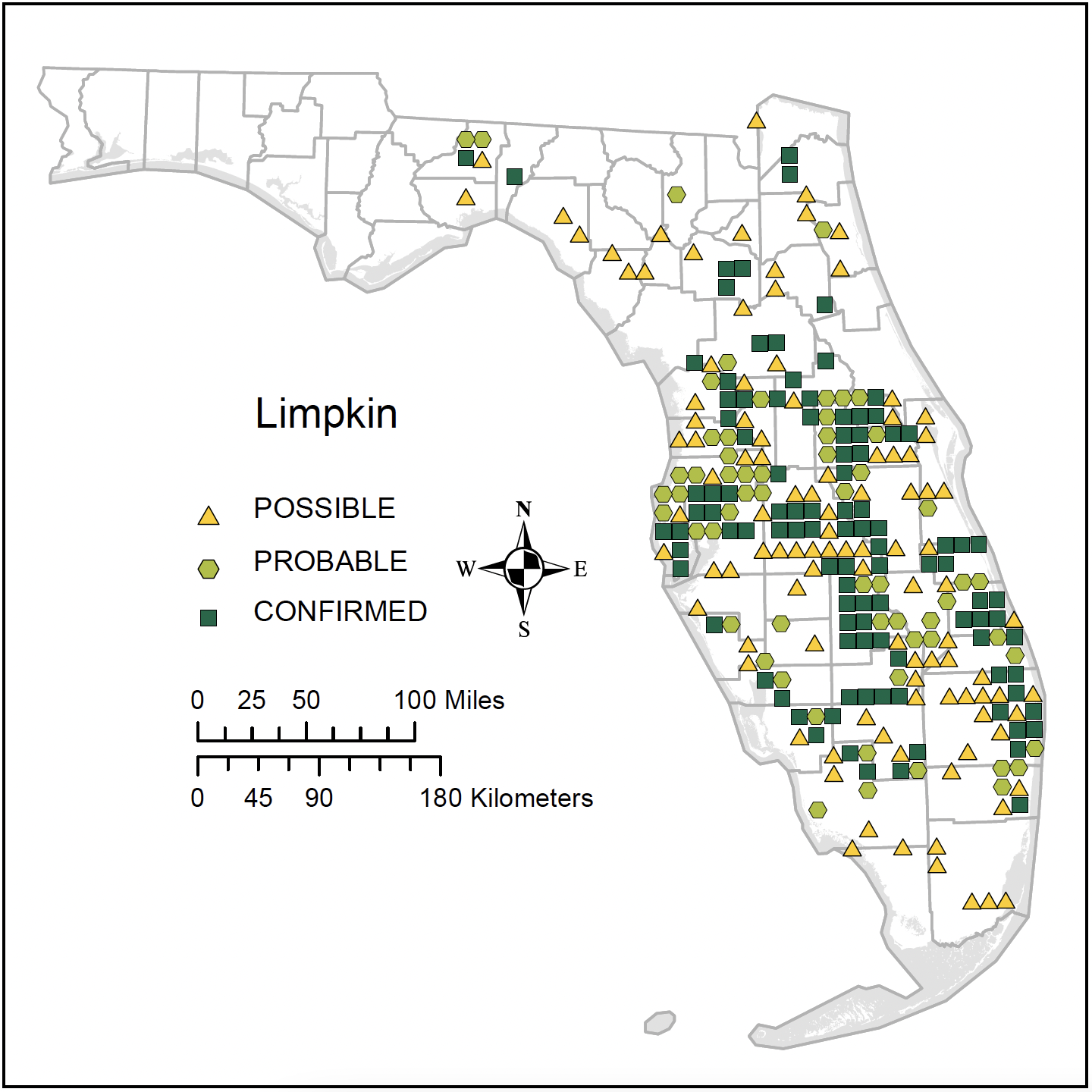

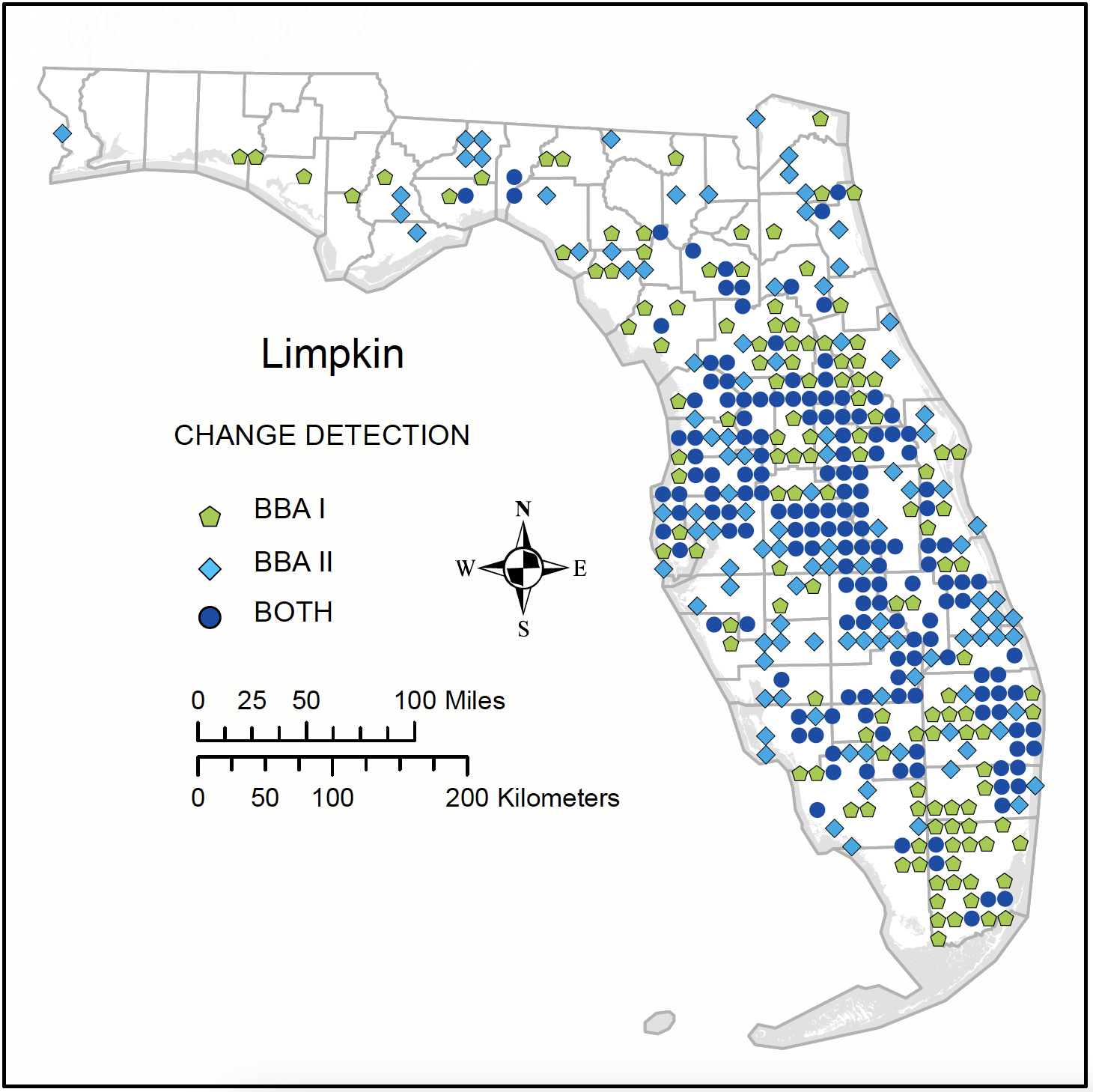

In both BBA I and BBA II, Limpkins were found throughout much of Florida. However, they live in wetland habitats suitable for apple snails, and these habitats occur more densely in central peninsular Florida than in the northern peninsula or the panhandle. Neither BBA I nor BBA II documented probable or confirmed breeding west of the central panhandle’s Ochlockonee River (Figure 1). Also, southernmost Florida (Collier and Miami-Dade counties) had fewer Limpkins than the rest of the peninsula both in BBA I and BBA II. Notably, in those 2 southern counties, although 15 probable or confirmed breeding blocks were recorded in BBA I, there were none in BBA II, suggesting a retraction in that area. This has been attributed to a local drought that killed off the native apple snails, which, for an unknown reason, did not recover. Unlike elsewhere, the exotic apple snails have not become established in the area (Paul Gray, Audubon Florida, personal communication). This change is also reflected in the total quad change comparison (Figure 2).

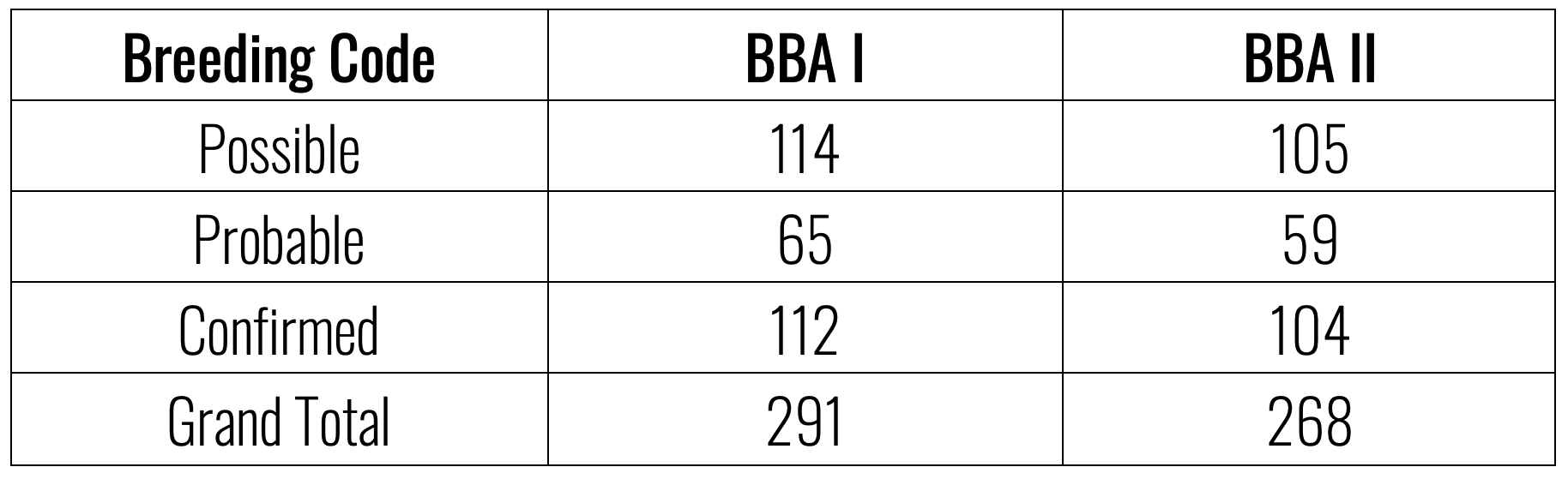

BBA II documents that the Limpkin population has expanded within central Florida but retracted in the northern and southern parts of the peninsula (Figure 2). Statewide, the lower number of records of all breeding codes in BBA II is likely the result of fewer quads sampled and the emphasis in BBA II on finding more species rather than confirming records. Compared with BBA I (Bryan 2003), confirmed breeding records in BBA II quads for the Limpkin were down 7.1%, and the total number of comparison quads having breeding codes was down 7.9% (Table 1). The growing Limpkin population and concomitant range expansion in parts of the state are widely attributed to the expansion of island apple snails since the late 1990s. As an example, the Limpkin population at Wakulla Springs (Wakulla County) was long considered a fairly isolated western-most stronghold of the bird, but by 2022 every lake and large holding pond in Tallahassee, 15 miles to the north, seemed to have a population of island apple snails and many had resident Limpkins. As another example, the annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count (CBC) for the Gainesville circle, centered in Paynes Prairie (Alachua County), reported Limpkin increases in less than a decade from 0 (2010) and 2 (2011), to 66 (2015), 235 (2017), and 540 (2018) (National Audubon Society 2020). Statewide, the CBC logged 92 Limpkins in 1991, the last year of the BBA I survey, compared to 3,020 in 2017, the last year of the BBA II survey. Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trends were not analyzed for Limpkin.

Data

Maps

Table 1

Quad level comparison of BBA I and BBA II based on the highest breeding code observed for a species within the 6 blocks of each quad.

Figure 1

Limpkin quad-level distribution, Florida Breeding Bird Atlas II. Figures 1 and 2 are based on data collected across all six atlas blocks within a quad. Figure 1 is based on the highest breeding code observed in each quad.

References

Benson, A. J. 2022. Pomacea maculata Perry 1810. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. U.S. Geological Survey, Gainesville, Florida, USA. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?SpeciesID=2633, Revision Date: 4/22/2019. Accessed 8 June 2022.

Bryan, D. C. 2003. Limpkin (Aramus guarauna). In Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, editor. Florida’s breeding bird atlas: A collaborative study of Florida’s birdlife. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tallahassee, USA. https://myfwc.com/media/19729/bba_limp.pdf.

Bryan, D. C. 2020. Limpkin (Aramus guarauna), version 1.0. In A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, editors. Birds of the world. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.limpki.01.

Dobbs, R. C. 2019. Limpkin Aramus guarauna (L., 1766) (Gruiformes, Aramidae), extralimital breeding in Louisiana is associated with availability of the invasive Giant Apple Snail, Pomacea maculata Perry, 1810 (Caenogastropoda, Ampullariidae). Check List 15(3):497-507. https://doi.org/10.15560/15.3.497.

eBird. 2021. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed 15 June 2022.

National Audubon Society. 2020. The Christmas Bird Count Historical Results [Online]. Available http://www.christmasbirdcount.org. Accessed 12 June 2022.

Rawlings, T. A., K. A. Hayes, R. H. Cowie, and T. M. Collins. 2007. The identity, distribution, and impacts of non-native apple snails in the continental United States. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-97.

Underwood, E. B., T. L. Darden, D. M. Knott, and P. R. Kinsley-Smith. 2019. Determining the salinity tolerance of invasive island apple snail Pomacea maculata (Perry 1810) hatchlings to assess the invasion probability in estuarine habitats in South Carolina, USA. Journal of Shellfish Research 38(1):177-182.