Methods

KEY POINTS:

- Fieldwork for the first Florida Breeding Bird Atlas (BBA I) occurred from 1986 to 1991 and the completed BBA I data are available on the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s (FWC) website (http://www.my.fwc.com/bba), including a description of the survey and analytical methods used, results, individual species accounts, and a discussion of the survey implications.

- Fieldwork for the second Florida Breeding Bird Atlas (BBA II) occurred from 2011 to 2016, with some surveys extended into 2017 to fill survey gaps. The completed BBA II data are available on the University of South Florida Libraries Florida Environment and Natural History (FLENH)/Florida Ornithological Society’s (FOS) web portal (https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/bba2/) including a description of the survey and analytical methods used, results, individual species accounts, and a discussion of the survey implications.

- Both BBA I and BBA II were designed to cover the entire state at the relatively fine scale of U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) 7.5-minute topographical quads, of which there are over 1,000 in Florida.

- Each topographic map was divided into 6 numbered blocks (each approximately 2,833 hectares [7,000 acres]) to partition each topographic quad for survey management.

- The BBA I survey protocol recommended that atlas volunteers spend at least 25 hours in an atlas block. In comparison, the BBA II survey protocol recommended that, minimally, atlas volunteers survey an atlas block until atlasers recorded approximately the same number of species (±10%) that were recorded in the block in BBA I.

- BBA II used “safe dates” that delimited seasonal periods when some breeding codes (e.g., singing male) could be used reliably to infer breeding.

- BBA II borrowed freely from other atlas projects and selected 20 breeding categories considered to be most appropriate for Florida.

- Volunteers entered BBA II field data into the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center’s BBA Explorer website.

- The BBA II production team members reviewed the BBA II raw data and culled records that did not fall within appropriate safe dates or use acceptable breeding codes as recommended by the North American BBA committee (e.g., wide-ranging raptors carrying food); individuals preparing the species accounts also reviewed BBA II data and suggested removing 8 extralimital records.

- Species Distribution maps and Distributional Change maps were produced for each species using ArcMap GIS.

- Additional records collected from other surveys (e.g., Florida Shorebird Alliance) were included in BBA II results where compatible.

- USGS North American Breeding Bird Survey data were used to examine trends in populations compared to the BBA II results.

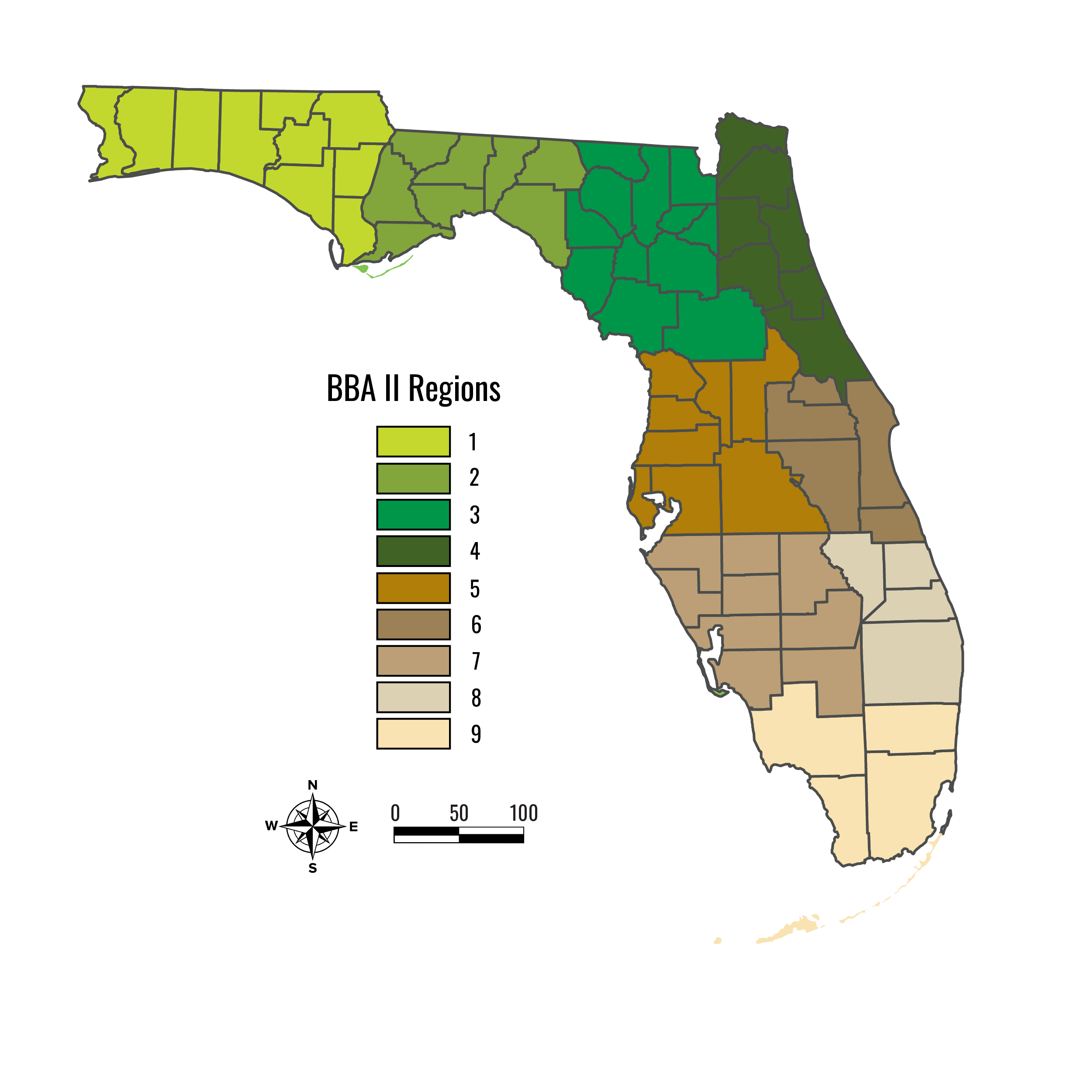

The first and second Florida Breeding Bird Atlas projects were conducted throughout Florida, including the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas. Administrative regions used in BBA II are shown below (Figure M1) and were different from the regions used in BBA I (FWC 2003). Public lands were accessed in coordination with their respective land management agencies. Access to private properties was dependent on permission granted by landowners and may have varied between BBA I and BBA II.

BBA II volunteers conducted fieldwork from 2011 to 2016 with additional work performed in under-covered areas in 2017. Rick West, statewide coordinator, and Florida Ornithological Society (FOS) volunteers administered the BBA II. While atlasers initiated some field work in 2011, FOS kicked off BBA II at the FOS spring 2012 meeting when Mark Wimer, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, introduced BBA Explorer, a new website developed by the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, to provide FOS and other organizations with tools needed to set up and conduct atlas projects. BBA Explorer featured on-line data entry and special queries to assess results for species by blocks, regions, and statewide. These tools made it possible for the volunteer participants overseeing BBA II to manage and process the data set.

Figure 1

The following sections describe the similarities and differences between the two atlas efforts to evaluate changes in breeding status and distribution of Florida birds. The methods used in BBA I (Kale et al. 1992) are available on the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s (FWC) website (FWC 2003; https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/bba/). The BBA I fieldwork was conducted from 1986 to 1991 followed by review and production of the web-based atlas. Thanks to a grant provided to Florida Audubon (now Audubon Florida) by the FWC’s Nongame Wildlife Program, BBA I had paid staff consisting of Herb Kale, the Florida Audubon Society’s Vice-President for Ornithology, and Wes Biggs, BBA I’s full-time coordinator. Kale and Biggs established regions for BBA I after hosting a series of regional meetings and developed a network of regional and county coordinators. The coordinators organized volunteers, assigned blocks, provided field data cards to participants, provided instructions for field methods, and conducted data review. Kale and Biggs also maintained a steady stream of public outreach through recurring newsletters, workshops, and meetings to further motivate volunteers conducting the work. Kale et al. (1992) estimated that there were 200 dedicated participants in BBA I.

Figure 3

Sampling Design

Citizen-science projects necessarily use tools and methods that are accessible and easy to implement. Sampling areas for BBA I and BBA II were based on the widely available 7.5-minute topographic maps (“topos”) created by the U. S. Geological Survey (USGS). The maps use 7.5-minute changes in latitude to create quadrangles (“quads”) approximately 13.7 km (8.5 miles) wide and extending over approximately 16,000 ha (40,000 acres). USGS topos include denotations of geographic features such as local roads, elevation, water bodies, rivers, forest cover, open spaces, and population centers that enable birders to stay within the boundaries of sampling units as they gather data.

BBA I atlasers sampled 1,028 topographic quads whereas BBA II atlasers sampled 1,033 topographic quads. The difference in the number of quads sampled is due to a difference in how some quads were managed; for example, 3 adjacent topographic quads encompassing the Dry Tortugas and Marquesas Key were merged into a single quad in BBA I but separated in BBA II. USGS also created an updated series of topographic quad maps in 2009 that included new maps for coastal areas with small accreting land areas in Florida. These minor changes account for the additional quads sampled in BBA II.

Each topographic map was divided into 6 numbered blocks (Figure M2; hereafter referred to as an “atlas block” or “block”) to focus on a smaller portion of each topographic quad that covered approximately 2,700 ha (6,700 acres; 11 sq mi). The blocks measure 4.7 km (2.9 mi) north to south and vary in east to west distance with latitude from 5.9 km (3.7 mi) near Pensacola to 6.3 (3.9 mi) in south Florida.

BBA I’s initial goal was to sample every atlas block in Florida (Kale et al. 1992). This daunting goal was later refined to sample at least 2 atlas blocks within each topographic quad. One of the atlas blocks tagged for consistent sampling was the southeastern block in the quad (Figure M2; “block 6”). This block was deemed the priority block for each quad, though exceptions were made for areas where block 6 was inaccessible or consisted mostly of (>50%) open water. For these quads, the next lower numbered block that qualified became the priority block for the quad. Priority blocks were targeted to be the most thoroughly surveyed areas within each topographic quad. A second block in each quad was selected by participants in BBA I based on the presence of distinctive habitats and other features not found in the designated priority block. Kale et al. (1992) expected this approach would produce a combination of random and nonrandom sampling across all quads. The sampling goals for BBA II (detailed below in Field Sampling) were derived from reviewing the data collected in BBA I. The theoretical maximum number of blocks for BBA II is 6,198 (1,033 quads x 6 blocks per quad).

FIELD SAMPLING

The BBA I organizers recommended that atlas volunteers spend at least 25 hours in an atlas block. This 25-hour recommendation was thought to be sufficient to enable an experienced observer to find most of the breeding birds in an atlas block containing a variety of different habitat types. In areas with little habitat variation (e.g., the vast marshes of the Everglades), atlas organizers suggested less time was needed. Access to different habitat types might be restricted in atlas blocks with few roads or dominated by private landholdings, so BBA I organizers established a second guideline for survey effort: (1) develop a list of species likely to breed in a block and continue sampling until ≥75% of the species were recorded, and (2) confirm at least 50% of the species. Kale et al. (1992) opined that this second guideline was probably used by most volunteers. Atlas volunteers were instructed to visit their quads and priority blocks at different times of the spring and summer to maximize the chances of finding breeding birds within the broad breeding seasons characteristic of Florida.

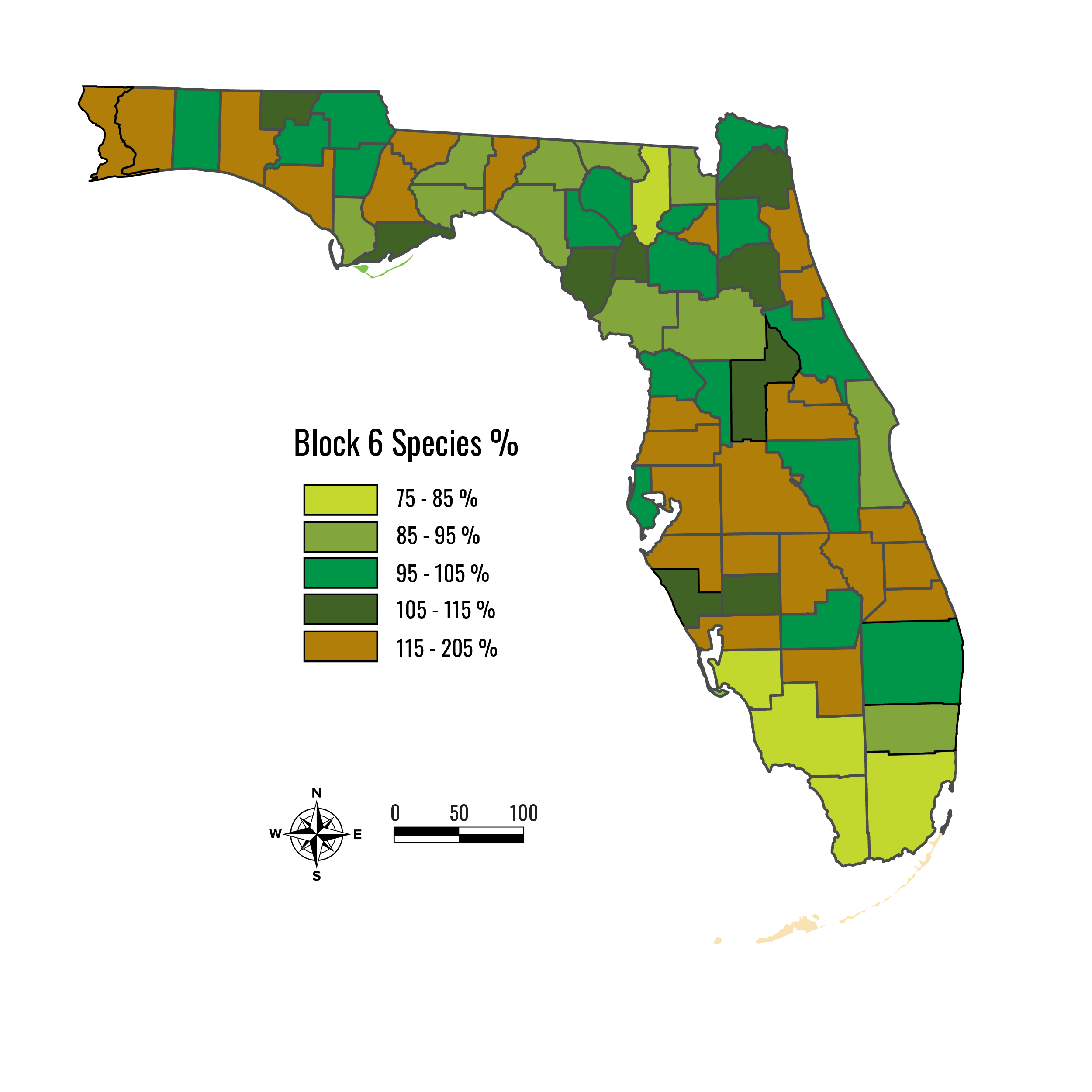

Records of the specific dates or times when surveys were conducted and/or the amount of time expended by volunteers were not recorded or archived for BBA I. From the BBA II Handbook, the minimum goal for fieldwork was to find approximately the same number (±10%) as in BBA I. Then, observers should cover all the habitats during the time of year the birds are breeding and at times of day when birds are most active. The first goal established for BBA II was to collect sufficient data for each priority block to provide statistical comparisons with BBA I. The metric used to assess data sufficiency was the average detection of as many species within each county, region, and statewide as recorded for BBA I. This objective was met statewide for BBA II where the number of species recorded in the priority blocks averaged 38.0 ± 14.9 and 37.3 ± 18.8 in BBA I and BBA II, respectively. The average ratio was calculated for each Florida county to provide a visual summary of the variation in survey effort suggested by the number of species detected (Figure M3); marked variation occurred in these tabulations at county and regional levels.

Relative to BBA I, survey efforts in priority blocks in BBA II regions 1, 2, 6 and 7 were approximately equal, but yielded fewer species on average among priority blocks in regions 3 (Leon, Madison, Taylor, and Wakulla counties), 4 (Columbia, Hamilton, and Suwannee counties), and 9 (Dade, Charlotte, Collier, Monroe, and Broward counties), whereas BBA II survey efforts yielded comparatively more species among priority blocks in regions 5 (Citrus, Lake, Hernando, Hillsborough, Pasco, Pinellas, Polk, and Sumter counties) and 8 (Martin, Okeechobee, Palm Beach, and St. Lucie counties). Species richness is just one measure of effort and could be affected by regional variation in the prevalence of declining vs. increasing species present and other factors, but variation in effort should be considered when evaluating changes in species distributions between BBA I and BBA II.

Other factors affected the quality of the data collected by the two atlases. During BBA I, FWC performed statewide aerial surveys for wading bird colonies and nesting Snail Kites and Bald Eagles. These data were merged with other BBA I data to provide more detailed information on the breeding distributions of these species than likely would have been collected exclusively by volunteers. FWC also assigned staff to gather data for BBA I during the final year of sampling (B. Millsap, USFWS [formerly FWC], personal communication), whereas a similar trove of paid atlas workers did not participate in BBA II.

BBA II also gathered additional information thanks to changes in technology: the advent of eBird led to a new source of information on species occurrences; the Florida Shorebird Alliance, which emerged in the wake of the Deep Horizon oil spill as a statewide citizen-science driven tool for recording shorebird nesting, aggregates breeding records of solitary and colonially-nesting shorebirds; FOS member David Simpson developed a keyhole markup language (KML) file that could be imported to both desktop and mobile devices to display Florida’s blocks and quads in Google Earth; and BBA II incorporated data from the USGS North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) routes as the digital data became available online (Sauer et al. 2020).

SAFE DATES

BBA II developed “safe dates” for most breeding species that delimited seasonal periods when breeding codes could be used reliably (i.e., after most spring migrants have departed but before most fall migrants have arrived) (See Appendix I, Table M1). BBA II used breeding categories, codes, and criteria based on Florida BBA I, where the categories are arranged in a hierarchical order from least certain (observed) to most certain (confirmed) (Table M2). Each species was assigned a pair of dates that restricted its inclusion in the atlas database for possible and probable breeding codes. If the species was seen outside this period, it was not considered to be a breeding bird unless specific breeding behaviors were observed. Codes affected by safe dates were SH (suitable habitat), SM (singing male), S (7 or more singing males), P (pair), T (territorial behavior), and SE (7 or more males singing on at least 2 dates, at least 1 week apart). Safe dates used for each species are included in the data set.

DATA PROCESSING

BBA II production team members, and individuals preparing the species accounts, reviewed the BBA II data. In this process, we searched for unusual records and other anomalies. For example, 2 observers who reported Bronzed Cowbirds in Madison and Escambia counties were contacted and they confirmed the records were data entry errors. This review led to censoring 22,442 records (Table M5; ca. 15% of total), which is comparable to the number of censored records reported for BBA I (Kale et al. 1992; ca. 20,000). The largest number of censored records in BBA II involved the use of an observation code rather than an acceptable breeding code (Table M5). This may have reflected some misunderstandings among volunteers on the application of this code, but most of these records (19,392) were colonial breeders and wide-ranging species (vultures) where higher levels of confirmation are required. We censored records of birds in suitable habitat (SH) and singing male (SM) that fell outside the safe dates (n = 890) established for each species. These procedures adhered to the guidance provided in BBA I: editing to comply with safe-date periods for species was unambiguous (Kale et al. 1992). Finally, individuals who prepared species accounts were also asked to point out questionable observations as part of their reviews (n = 20). These procedures followed similar steps taken in BBA I to limit the number of transcriptional errors, especially for extralimital observations that lacked additional verification. The final set of edited records for BBA II included 125,931 total records, but many of these featured observed codes that are not typically considered breeding records (Laughlin et al. 1990). The FWC BBA I database features 134,965 records with only a handful of observed codes retained.

MAP PRODUCTION

Distribution and Change Detection maps were produced for each species using ArcMap GIS. Topographic quads were selected as the map units to comport with maps available on the FWC web site (FWC 2003). Distribution maps displayed the highest breeding code observed for the species in each topographic quad in which it was recorded. Change Detection maps compare the simple presence/absence of the species within a topographic quad between both atlas efforts. This approach is consonant with the FWC maps (FWC 2003) while also avoiding some of the inherent variation in some of the breeding codes that were used (e.g., S and SE). Individuals with color-vision deficiencies reviewed several different symbols and color combinations to provide ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) support. The symbols and colors selected adhered to similar hierarchies for breeding and change detection maps (Figures M4a and M4b).

NORTH AMERICAN BREEDING BIRD SURVEY

The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) is one of the premier bird monitoring programs in the world. Started in 1966 by Chandler S. Robbins, data are collected by experienced volunteer birders following a standard protocol of 3-minute point counts at 1/2-mile intervals on a 24.5-mile route (Sauer et al. 2017). All birds seen or heard within a 0.25-mile radius are recorded for each counting location. The data collection points along the route are the same every year. Data collected on the routes are submitted to the BBS office (USGS, Laurel, Maryland, USA) for entry and storage. These data are publicly available via the BBS website (https://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/).

BBS data for 60 to 100 routes have been collected in Florida every year from the inception of the survey. Data were obtained from the BBS website for bird species at both the scale of the entire survey or a single state in the form of the average number of individuals of a species recorded per route per year. Not all breeding birds in Florida have enough data to be posted on the BBS website. For species that had sufficient data, we overlaid plots of the average number of individuals per year at both surveywide and Florida only levels. The ongoing BBS provides a valuable “second opinion” for changes observed in the intermittent and more labor-intensive Breeding Bird Atlases. Also, some data on individual species collected during the period of BBA II were used to supplement data collected by BBA II volunteers.

OTHER DATA SOURCES

Additional data from other surveys and projects were included in BBA II results where they were compatible. The USGS Breeding Bird Survey data (Ziolkowski et al. 2022; 8,721 records) was the largest source of data, but we also used data from eBird (2017; 1,891 records), the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (>513 records), wildlife/bird rehabilitation centers (370 records), Ecostudies Institute’s mangrove data (721 records), the Center for Conservation Biology’s Nightjar Survey (91 records), and many records from the Florida Shorebird Alliance and the South Florida Water Management District. Some additional data were retrieved from surveys for endangered species, such as the Red-cockaded Woodpecker and Crested Caracara.

BBAII BIRD SPECIES TAXONOMY

To establish the scientific and common names of birds and their taxonomic order for BBA II, we relied on the Official Florida State Bird List prepared and maintained by the Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee (FOSRC; https://fosbirds.org/florida-bird-list.html). This list, in turn, follows the order and nomenclature of the American Ornithological Society (AOS; Chesser et al. 2021). For species not included in the FOSRC or AOS lists, we used the taxonomic order provided by the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Birds of the World (https://birdsoftheworld-org.proxy.birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home). Taxonomic changes between BBA I and BBA II are tabulated in Appendix 2: Table M6. Although the taxonomic system used to name and list the birds in the species accounts in BBA I was not specified, readers should note that the taxonomic classification of some species (e.g., Least Tern), families (e.g., Anatidae), and orders (e.g., Ciconiiformes) changed in the period between BBA I and BBA II.