Species Account

The Osprey is the only member of its genus, Pandion, and family, Pandionidae. Its distribution is cosmopolitan, occurring on all continents but Antarctica (Winkler et al. 2020). In North America, its breeding range includes much of Alaska and Canada, the Pacific Northwest, and extends down the coasts to Baja California and through the Caribbean (Winkler et al. 2020). Osprey are considered of least concern by the IUCN and their populations and ranges are generally increasing (Bierregaard et al. 2014, Poole 2019, BirdLife International 2022). They live near bodies containing shallow water (BirdLife International 2022).

Fish make up the overwhelming majority of the Osprey diet (Hakkinen 1978, Cartron and Molles 2002, Silva e Silva and Olmos 2002, Beech 2003), with mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates contributing an estimated ~1% (Wiley and Lohrer 1973, Martins et al. 2011). In inland populations, where alternative prey may be abundant, Ospreys may feed on non-fish prey more frequently (Wiley and Lohrer 1973). Prey-drowning has been observed in an inland Florida Osprey and this behavior could facilitate the exploitation of air-breathing prey (Tringali and Brown 2020).

Banner Photograph: Alexander Lamoreaux

Illustration: Diane Pierce

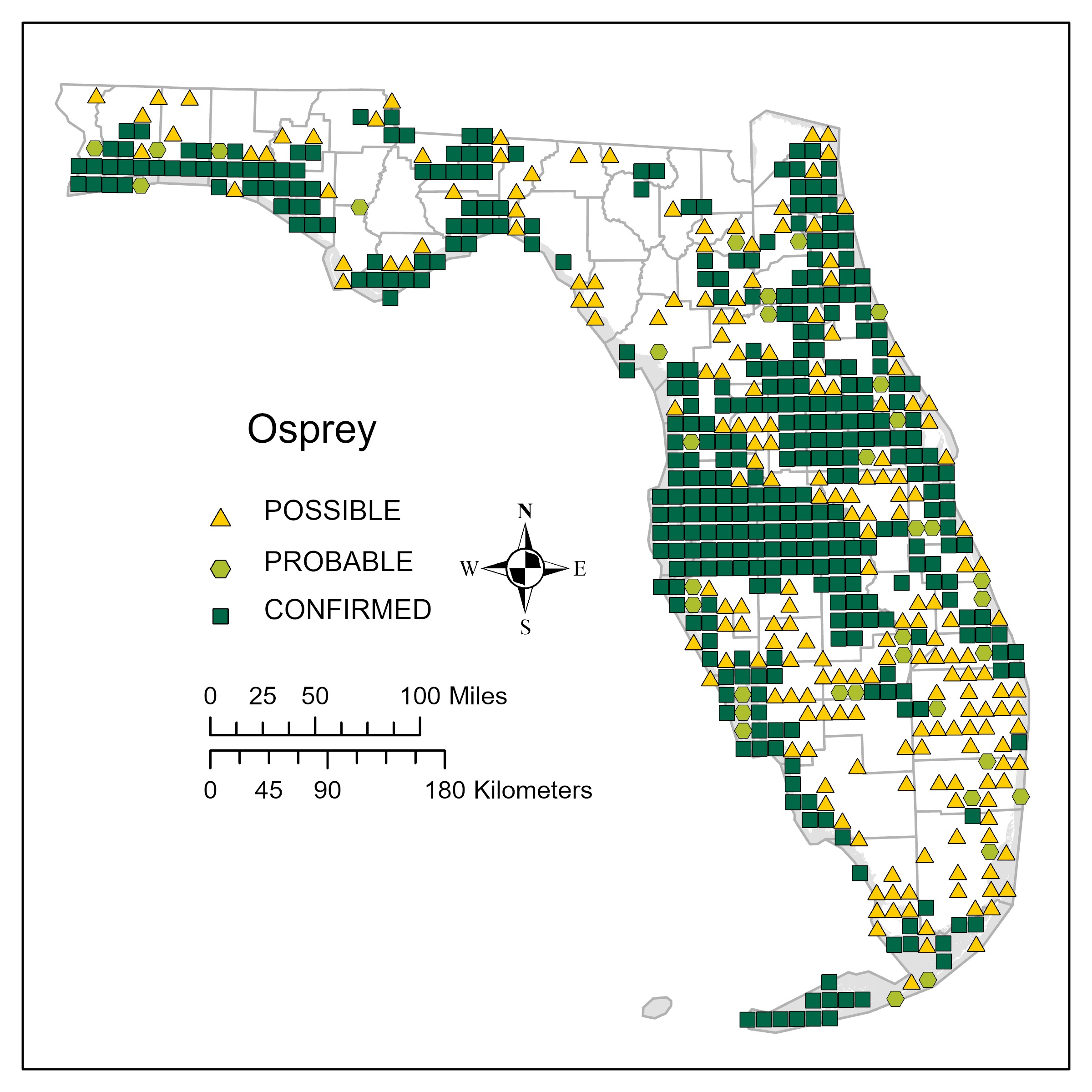

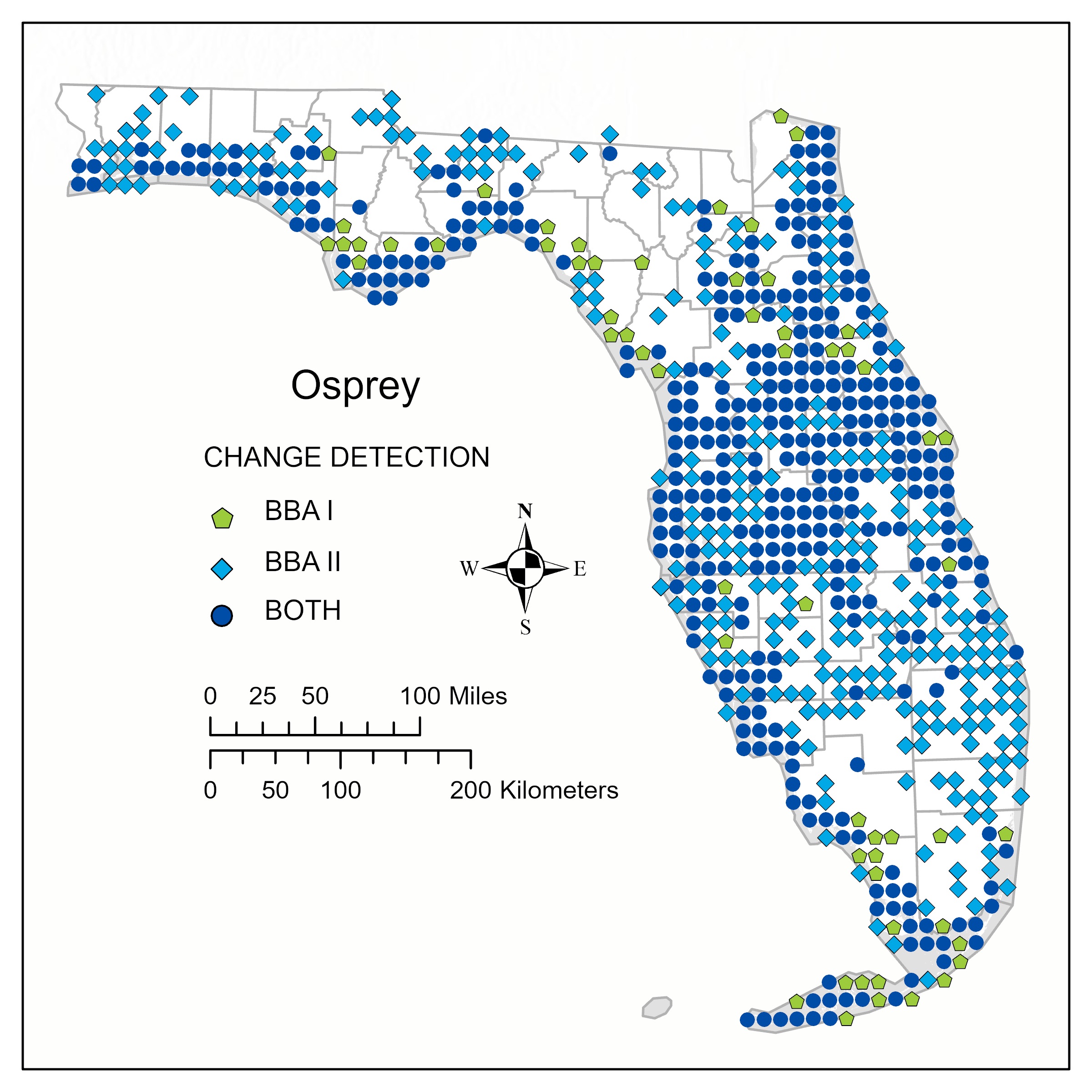

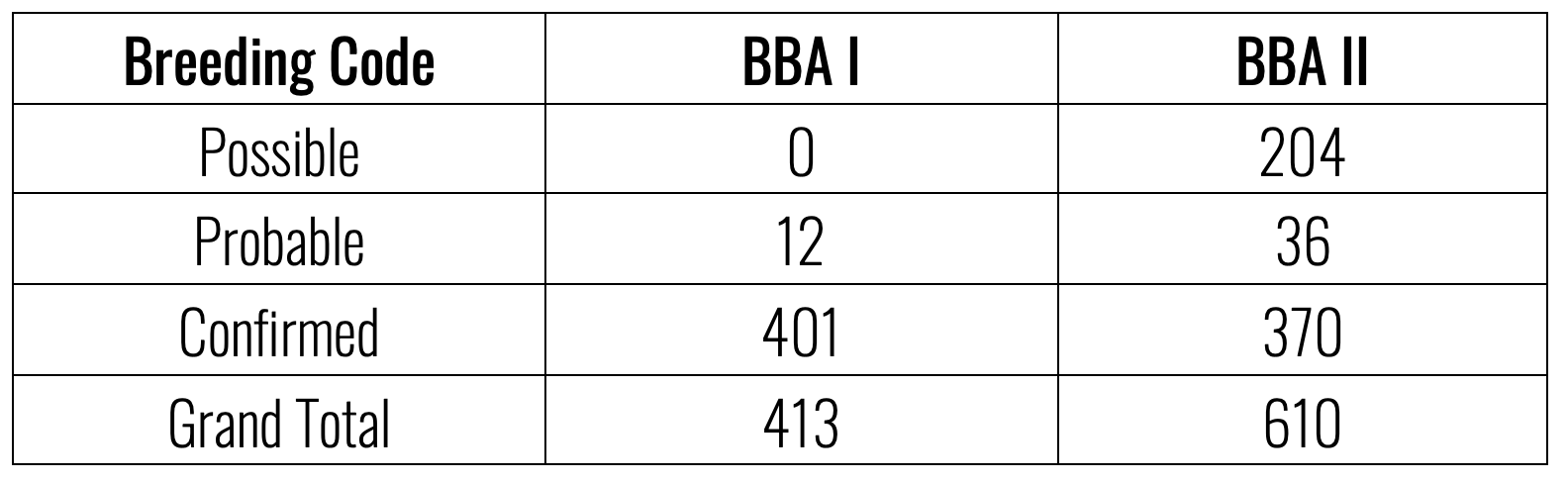

As in other parts of its range, the Osprey is expanding in Florida. The number of quads that contained breeding codes increased by 48% from 413 to 610 (Toland 2003; Table 1). The number of possible and probable breeding records increased, with confirmed records decreasing by about 8% (Table 1). The lower number of confirmed records in BBA II is likely the result of the emphasis in BBA II on finding more species rather than confirming records. Comparing BBA I and BBA II, it is apparent that much of the Florida range expansion has occurred inland (Figure 1), especially in the panhandle, southeastern Florida, and inland south-central Florida. However, some quads that were occupied in BBA I were not in BBA II, and these are particularly noticeable along the Florida keys and Gulf Coast along the panhandle and Nature Coast (Figure 1).

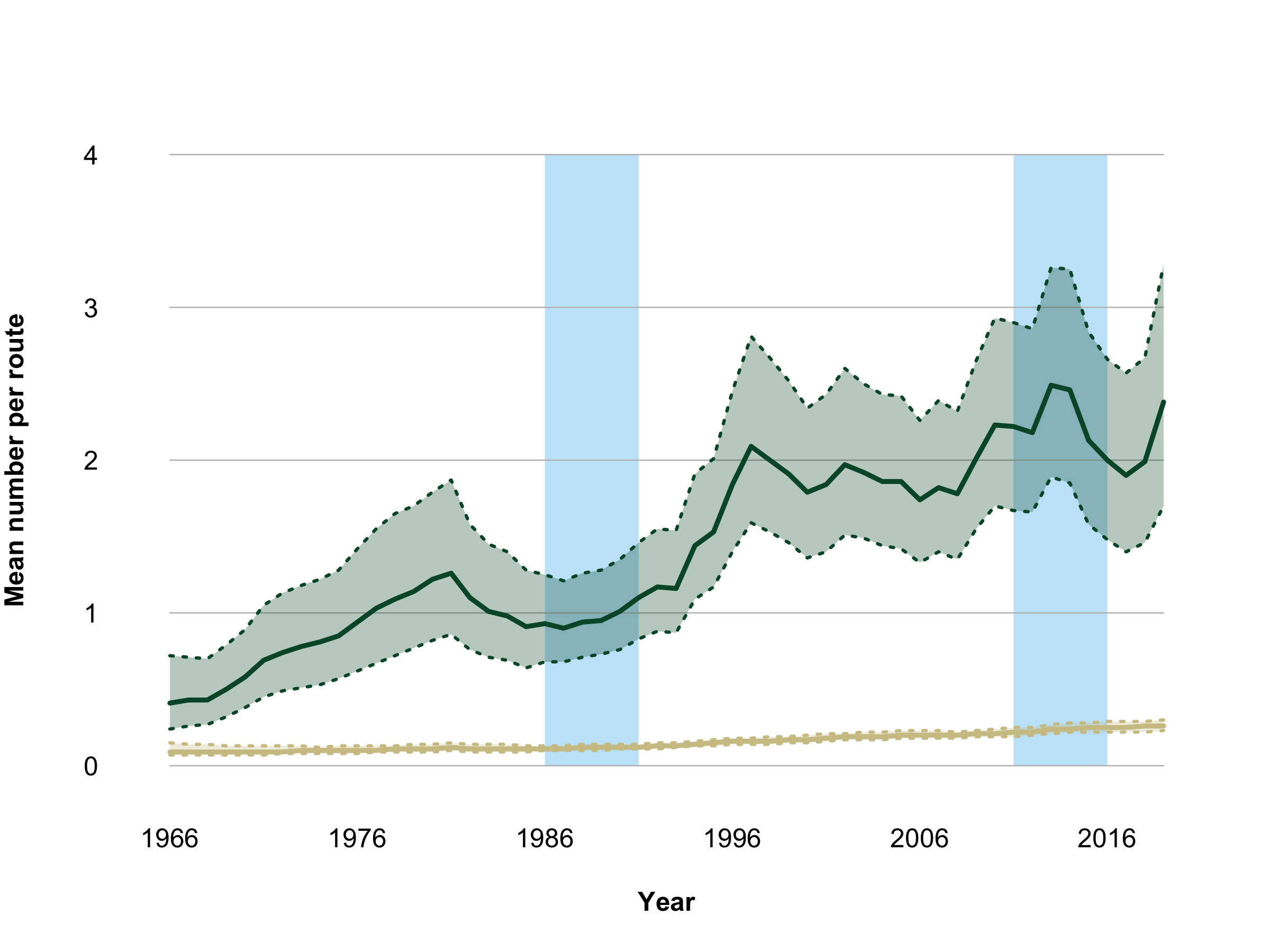

The observed range expansion was accompanied by an increase in Osprey population size, both survey-wide and in Florida (Figure 2). The increase in Ospreys on Florida Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) routes is more pronounced than the survey-wide increase, from about 1 per route in BBA I to more than 2 per route in BBA II (Figure 3).

Ospreys were in danger of extinction in the mid-twentieth century, but since DDT was banned in 1972 their populations have rebounded (Poole 2019). In Florida, Osprey populations have increased, and their range has expanded, mostly inland. Ospreys will readily use nesting platforms and these platforms are often built to discourage Osprey from nesting on power lines, road signs, and other structures. This inland expansion may be facilitated by the construction of nest platforms along roadways and powerlines (Houston and Scott 2001) or other human-modified structures, such as reservoirs (Airola and Estep 2022). Their range expansion could also be facilitated by behaviors allowing them to exploit alternative foods.

Data

Above photo by Alex Lamoreaux

Table 1

Quad level comparison of BBA I and BBA II based on the highest breeding code observed for a species within the 6 blocks of each quad.

Maps

Figure 1

Osprey quad-level distribution, Florida Breeding Bird Atlas II. Figures 1 and 2 are based on data collected across all six atlas blocks within a quad. Figure 1 is based on the highest breeding code observed in each quad.

Figure 3

References

Beech, M. 2003. The diet of osprey Pandion haliaetus on Marawah Island, Abu Dhabi emirate, UAE. Tribulus 13:22-25.

Bierregaard, R. O., A. F. Poole, and B. E. Washburn. 2014. Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) in the 21st century: populations, migration, management, and research priorities. Journal of Raptor Research 48(4):301-308.

BirdLife International. 2022. Species factsheet: Pandion haliaetus. http://www.birdlife.org. Accessed 18 July 2022.

Cartron, J. L. E., and M. C. Molles. 2002. Osprey diet along the eastern side of the Gulf of California, Mexico. Western North American Naturalist 6d2:249-252.

Hakkinen, I. 1978. Diet of the Osprey Pandion haliaetus in Finland. Ornis Scandinavica 9:111–116.

Houston, S. C., and F. Scott. 2001. Power poles assist range expansion of Ospreys in Saskatchewan. Blue Jay 59(4):182-188.

Martins, S., R. Freitas, L. Palma, and P. Beja. 2011. Diet of Breeding Ospreys in the Cape Verde Archipelago, Northwestern Africa. Journal of Raptor Research 45:244–251. doi:10.3356/jrr-10-101.1.

Poole, A. F. 2019. Ospreys: The Revival of a Global Raptor. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Sauer, J. R., W. A. Link, and J. E. Hines. 2020. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, analysis results 1966 – 2019: U.S. Geological Survey data release. https://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/.

Silva e Silva, R., and F. Olmos. 2002. Osprey ecology in the mangroves of Southeastern Brazil. Journal of Raptor Research 36:328–331.

Toland, B. R. 2003. Osprey (Pandion haliaetus). In Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, editor. Florida’s breeding bird atlas: a collaborative study of Florida’s birdlife. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tallahassee, USA. https://myfwc.com/media/19754/bba_ospr.pdf.

Tringali, A., and R. A. Brown. 2020. Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) drowns eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). Florida Field Naturalist 48:12-13.

Wiley, J. M., and F. E. Lohrer. 1973. Additional records of non-fish prey taken by Ospreys. The Wilson Bulletin 85:468–470.

Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette. 2020. Osprey (Pandionidae), version 1.0. In S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, editors. Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.pandio1.01.